|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Following Murukan: Tai Pucam in Singaporeby Gauri Parimoo Krishnan

Click on images to view at full size or go to: Archival photo gallery: Tai Pucam in Singapore.Color photos by Kuet Ee Foo

|

|

| An archival photo of a devotee carrying a kavadi taken in the 1940s. © National Archives, Singapore |

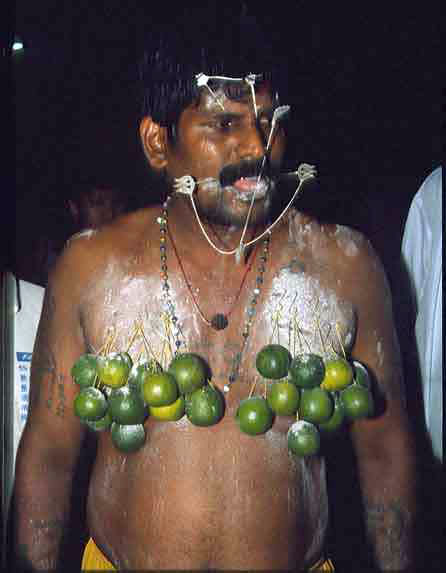

A survey of back issues of Tamil Murasu,27a local Tamil language newspaper, was conducted to ascertain the discontent and skepticism among reformist Hindus about following folk and crude practices in the days when TRA was active. Some comments and candid photos flavoured with sarcasm and arousing the readers to sit back and think. The caption of a photo of TM, Jan-Feb 1940, page 5 of the Murukan devotee with small pots hooked to his chest reads: "Hey Shanmuga? What sin did this man commit? In order to bear so many pots?" A picture of two devotees bearing the belt kavati are illustrated in TM, Jan-Feb 1940, page 7 with the caption on the side reading: "Devotees who experience hell on earth in order to attain salvation in heaven! Two scenes of Tai Pucam in Singapore." Yet another comment is candid from TM, Jan-Feb 1940, "Devotees who believe in receiving the grace of Arumuganathan through self-torture by piercing needles and spikes through their bodies, instead of undertaking genuine devotion."

Even Periyar, the grand old man of Tamil Nadu is quoted in TM, 7 January 1955, page 2 "Is it right to carry alagu kavatis? Tamilians?" He is cited as underlining the importance of education and denouncing the practice of dancing and carrying kavatis. He expressed his dislike for piercing alagu kavatis.

In later issues of the Tamil Murasu, the tone was much tolerant and the caption for one photo in TM, 20th January 1983, page 8 read "Many boys bore kavatis. Their bhakti and enthusiasm were immensely evident. This is one such kavadi bearer." This shows that over the past several decades, the opposition for kavati carrying and body piercing has declined as more and more educated, wealthy, successful and businessmen

|

| A Chinese devotee with his elaborate kavadi is not a rare sight during Thaipusam in Singapore. © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore |

Both these festivals continue to be significant cornerstones of the Hindu religious tradition in Singapore today according to Sinha.29 It needs to be highlighted at this stage that these festivals have been promoted by the Singapore Tourism Board as well and they catch the fancy of the public through media but there are many more festivals that Hindus perform which are accorded theological and ritualistic significance in Singapore.

The case in point is kumbabhishekam and brahmotsavam festivals, which most established temples have celebrated from early on. Festivals such as Mahashivaratri, Krishna Jayanti, Navaratri and Ramanavami over and above certain folk festivals in honour of village deities of South India such as Periyacci, Aravan, Aiyenar, et al. are celebrated in a big way in which many devotees participate. Since these festivals are confined to the temple premises, they do not get much media attention. Thus to call the above mentioned festivals as 'cornerstones' of Hinduism in Singapore is a misleading interpretation of collective Hinduism.

Tai Pucam in Singapore

|

| Devotees carrying their kavadis arriving at the Thandayudhapani temple, Tank Road. © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore |

The history of Tai Pucam is closely associated with the Thandayudhapani Temple, which was established by the Chettiars30 in 1859. To this day it is closely linked with the moneylender, merchant, banker, and trader community. According to Chettiar sources31 and referred by early historians of Singapore like C.M. Turnbull32 a small shrine was constructed by the bank of a tank formed by a waterfall on what is generally known as Tank Road. A vel, spear brought from India as early as mid-19th century was established under a peepal tree, which was uprooted for urban redevelopment in recent times. The foundation stone at the temple refers to its consecration on 4.4.1859. The land for the temple was acquired from Mr. Oxley, the first Surgeon General of Singapore.

The temple was modest, having an ālankara mandapa and ardhhmandapa. Jambu Vinayagar and Itumban shrines were placed on either sides of the main sanctum. Two separate shrines for Shiva and Meenakshi were consecrated in 1886, although they were constructed in 1878. A dining hall was also constructed called karttikai kattu where food was served during Tai Pucam and Karttikai.

Chettiars have built temples to Murukan wherever they settled in Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaya, Sri Lanka and Singapore. Here panhtarams could be employed who could perform rituals and filled the gap for Brahmin priests who were prohibited from travelling overseas.33 Here it should be noted that the role of the Chettiar and the other members of the Hindu society in Singapore open up an interesting parallel and co-existence of Hindu faith. The participation and dissociation from each other of different communities in one and the same festival poses different perspectives of viewing and sharing of the God, the faith and the blessings.

The earliest Hindu temples in Singapore were situated around the pockets of Indian villages around Tanjong Pagar area where most port workers lived and congregated and where the Malayan railway station was also situated. The railway connected Singapore to Kuala Lumpur and Penang. Mari Amman temple in South Bridge Road (established in 1862), Sivan temple on Orchard Road (established in 1850s) and the Chettair temple on Tank Road (established in 1859) are in close vicinity of Tanjong Pagar area.

By mid 19th century, there were seventeen Indian businessmen of standing in Singapore comprising Parsis, Tamils and North Indians. They were known as individuals and not as community leaders, except, of course, Narain Pillai who was instrumental in building some of the earliest temples. Most of the Indians were labourers, ferrymen or petty traders. Towards the end of the 19th century, there was an increase in the number of Indians who came as traders, shop assistant and clerks. Indians also worked as boatmen, dock coolies and bullock-cart drivers.34 Thus the population of Indians was very complex and it fitted very well into the social, economic, cultural and political matrix of Singapore.

In most places in Singapore and Malaysia, Tai Pucam is a three-day festival. In Singapore, it is jointly organised by the Hindu Endowments Board and the Thandayudhapani Temple on Tank Road managed by the Chettiars. It is promoted by the Singapore Tourism Board as one of the main attractions in the Post Christmas-Chinese New Year period.35 Many foreign visitors and Indians unfamiliar with this festival view this with amazement, doubt and skepticism. For avid Asian culture savvy photographers this is one golden chance to capture ethnic Indian practices without going to India. For those interested in documenting this festival, it is an experience of dichotomous existence of tradition and modernity in the lives of ethnic Indians, which is often debated by Indians themselves. We at ACM have conducted documentation of the festival since 1996, sometimes partially and sometimes at a stretch for three days in Singapore, Malacca and Penang.36

On the day prior to Tai Pucam, the utsava mūrti or bronze icon of Murukan is taken in a chariot, which is cleaned and decorated once a year for this occasion. It is dragged through the streets of Singapore and taken to the Vinayakar temple on Kiong Siak Road near the Mari Amman temple in South Bridge Road or Chinatown. In the evening the chariot returns back to Tank Road after meandering through the financial district stopping before Indian Bank, UCO Bank and other financial institutions. In the past the chariot used to pass through Market Street on which most Chettiar kittangis, workplace-cum-lodgings of the Chettiar community were located.

The Chettiar devotees used to offer plates with offerings of coconuts, flowers and betel leaves. There are some interesting oral accounts of how garlands were offered by puppet dolls or angels tied to ropes and slide down towards the chariot which were caught by the priest standing near the deity on the chariot.37 Many people follow the chariot either singing bhajans or simply walking as part of a personal vow. Most Chettiar devotees who have vowed to carry their kavatis follow the chariot. They prepare their kavatis in the Vinayakar temple at Kiong Siak Road in the morning and towards evening after performing ārati and preparing Vinayakar pongal, begin their journey towards Tank Road before the chariot rolls off. A pongal is also prepared before the kavati is taken followed by recitation of kavati cintu, in which women also participate.

The Chettiar kavatis are taken to the Mariamman temple on their way to the Thandayudhapani Temple on Tank Road. After reaching Tank Road before midnight, many devotees dance with their kavatis and the utsavar is made to rest on a platform in the mandapa inside the Thandayudhapani Temple. Early next morning, the kavatis are taken out again around the temple on the nearby River Valley Road and Killney Road when Chettiar ladies carrying pālkutams, milk pots, also join in. Finally brown sugar from the pots is mixed to form the pancāmritam and abhishekam is offered to the main idol (which is in the form of a vel) and prasādam is distributed.

|

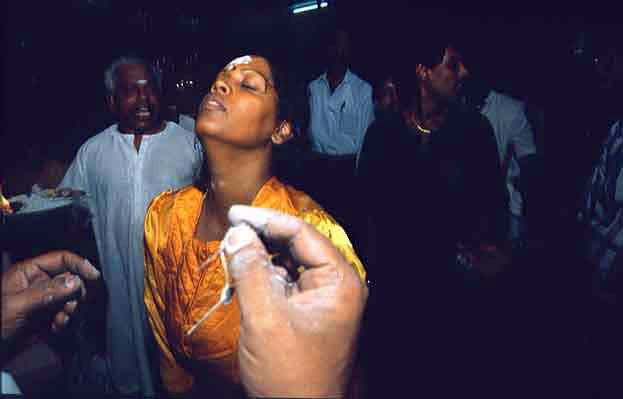

| A devotee prepares for maunam, the vow of silence. © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore |

As for the other Hindus, they begin to congregate in the courtyard and the adjoining mandapam grounds of the Shri Shrinivas Perumal Temple on Serangoon Road since late night. They arrive in groups and the crowds swell by midnight. People set up their individual puja to Vinayakar by offering fruits and vettulai paku (betel leaves and aracca nuts) before taking their milk pots palkutams or kavatis. Milk is then poured into milk pots and a yellow cloth is tied over the mouth of the pot. Some devotees also get themselves pierced by tiny vels on the forehead and the tongue, which is the most important aspect of the ritual discipline. As rightly observed by Carl Vadivella Belle, "they indicate firstly that the pilgrim has temporarily renounced the gift of speech (the vow of silence, maunam) so that he/she may concentrate fully on Murukan and secondly that the devotee has passed wholly under the protection of the deity, who will not allow him/her to shed blood or suffer pain. By permitting the vel to pierce the flesh the aspirant is indicating the transience of the physical body as opposed to the enduring power of truth."38

The devotees carrying palkudams and the traditional kavatis are allowed to proceed on their journeys by about 2.30 am, while the larger kavatis with larger vels pierced through the devotees' bodies begin to move around 4.30 am. Devotees come in batches and until after midnight on the day of Tai Pucam kavatis are taken from the Perumal Temple in Serangoon Road to Tank Road. A continuous abhishekam is conducted at the Thandayudhapani Temple where the milk pots are offered and the kavatis are dismantled in the field opposite the temple. According to HEB records about 3000 participants take part in this annual pilgrimage festival.

Kavatis are carried not only in honour of Murukan but also for other Hindu deities as well, including Mariamman, Durga, Vinayaka, Shiva, Krishna, Rama, and Hanuman. Other village and guardian deities are also invoked such as Muniandi, Munīsvaran, Madurai Veeran, Sinnakarupan, Karuppanaswami, et al. A vow to carry kavati or palkutam may be prompted by a devotee's decision to overcome an unfavourable situation or for thanksgiving after achieving desired result. Illness, academic success, wealth and family harmony are the main areas which concern the vow taking kavati bearers, who fulfil their vows regardless of caste, creed, colour, religion, racial or socio-economic backgrounds.

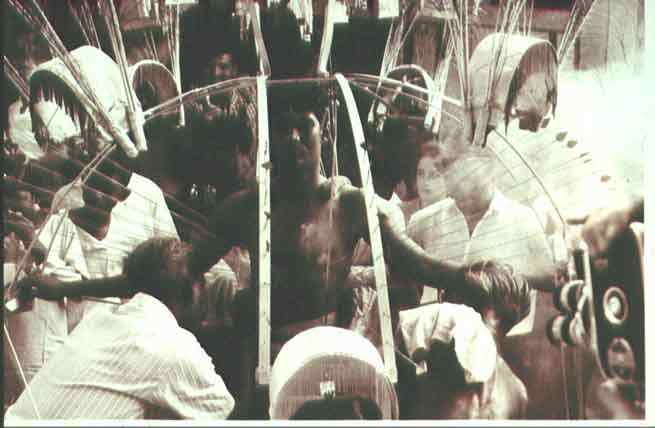

From photographic evidence it can be said that from 1920s onwards body-piercing with small vels has been practiced in Singapore. But a very primitive form of spiked kavatis worn with a belt was started by migrant Indians in Singapore and Malaysia only in the 1940s. This kavati was held atop the head by four vertical spikes which were worn around the waist tied to a belt. The kavati usually designed in circular shape was decorated with plumes of peacock feathers, images of Murukan and other gods, decorative patterns and colourful materials.

From my informants I gather that in Singapore a special type of kavati was invented which is called arikanti, in which the two-meter long vertical spikes are not held in place by the belt but pierced in the muscles of the stomach and the back. Arikanti is the type of kavati in which there is no belt but four vertical metal rods are pierced through the stomach and the back around the waist on which the upper structure of the kavati rests. The whole structure when balanced properly heaves as the devotee walks simulating the gait of a peacock with a fanned out plumage.

From the Kampong Bahru people I learnt that it was one Kottai Katti who invented arigandi kavati. This was an innovation that had risk involved but slowly became popular. It was further popularised by one Vathi of Kampong Bahru from 1950s onwards and since then it has come to be known as Vaithi kavati. Today we see many devotees carrying this type of kavatis. This way of bearing the heavy weight of the kavati requires not only experienced gurus or helpers to pierce but the devotee himself should also be very committed and faithful.39

In my informant's summation the most important thing during Tai Pucam is to note the seasoned kavati or janma kavati, which has been carried on since many generations and passed around in the family and near friends. Very few such kavatis are remaining now in Singapore. Filial commitments and responsibility play a significant role in supporting the kavati bearer, who could be one's own father, brother, husband or cousin. One cannot miss noticing family and friends helping the devotees at every stage, accompanying them in the preparation and throughout the journey by singing, chanting, inspiring and encouraging them. As my informant explains, this is a matter of social and emotional dynamics at play where a family works together to achieve a common goal by understanding each other's strengths and weaknesses. It has to be seen to believe that a major ritual like lifting a kavati cannot be fulfilled by the devotee alone, but requires divine intervention and family support.

The devotees lifting kavati observe a fast from three days to forty-eight days depending on their circumstances. They do not shave or cut nails and observe vegetarian diet, celibacy and abstain from other worldly comforts. Kavati and all the related apparatus are worshipped before the kavati is carried in the presence of Murukan and invoking Vinayakar. The closing of the festival is celebrated by worshipping Itumban who, it is believed, gives the devotees the brute strength to lift such a load. Thus over and above Murukan, it is Itumban who is invoked during the kavati festival to impart strength to the devotee and to protect him during his entire kavati ritual. 40

|

| A devotee in a state of trance as she prepares herself to be pierced on her forehead. © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore |

Most kavati bearers come into a state of trance. They are under the grace of Murukan (called arul, state of grace) which can be seen from their physical gestures such as trembling, swooning, going into a deep concentration oblivious to the surrounding people and the noise. Chanting, music and drumming enhance this. Especially when the first vel is pierced in the forehead, the devotee must submit himself mentally to the grace of Lord Murukan and only then will the piecing be smooth and painless.

The miracle of bloodless piercing can also be ascribed to the divine grace of Murukan. The trance can be described as a state of void or amnesia. In the words of Carl Vadivella, "after the initial trance recedes (it) is replaced by a condition the devotee reports as a form of heightened 'supercharged' awareness. In this state the devotee is cognizant of all that is happening around him/her and is able to respond positively to directions, but feels him/herself to be operating at a level which is infinitely superior to mundane consciousness. This has also been my own experience."

An important part of the kavati ritual is the mental, physical and ritual preparation, each having a particular significance. The kavati, its various components, the image of Murukan which is carried atop the head and a miniature vel which is symbolically supposed to represent Itumban are arranged in a row and then prayers, fruits, flowers, dhoop and deepam are offered to it. A special mixture of pori, avval, honey, lentils, cashews, raisins, homam water, etc., is offered as prasadam.

The devotee lifting the kavati is bathed with turmeric water and lemon is cut above his head and waved in a circular fashion around their whole body to remove any bad drishti or omen. After this the kavati bearer begins his prayers and asks for pardon. It usually at this stage that the first vel is inserted into the forehead for concentration by an experienced man who is prearranged and who is usually familiar with the family.

In the state of trance or the 'supercharged state', the devotee may ask to breath burning sambhrani and karpuram from time to time, to smoke a cigar and speak some words which only some veterans of the group helping him know to interpret. After this the dhoti, head cloth, etc., are tied and the belt fixed to the waist.

The most important part of the kavati 'dress-up' on one's own body is the installation of the icons of Murukan and the vel for Itumban. Thus the devotee becomes a carrier or a vehicle himself and the act of lifting the kavati is almost akin to assimilating spirit of the divinity within one's self and impersonating as a peacock or as Itumban. Throughout the journey the devotee carries the icon of his beloved deity on his head and all he aspires to view is the milk poured on the idol of Murukan inside the shrine where he reaches after an arduous journey.

This is a moment of great joy. Many devotees associate this act as a humbling experience and believe that the vel is a dispeller of ignorance and ego. Some of them feel they are recharging themselves, or purifying themselves as well as praying for the well being of their family and friends.

|

| The Itumban puja performed at a devotee's home, marking the end of the festival. © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore |

The last part of the kavati puja is the worship of Itumban and breaking of the fast. As the gatekeeper and a devotee of Murukan, Idumban is offered salutations for making the whole journey smooth and for successfully completing the vow. This ritual marks the completion of the vow taking and allows for a smooth passage into normal daily life. It is also a festivity and lot of delicious food is offered to Itumban. A cockerel is sacrificed and non-vegetarian food is cooked on this day. This is normally celebrated immediately after Tai Pucam or a week after where many kavati devotees gather together in one place and perform the ritual jointly.

Concluding Remarks

According to many Murukan scholars and devotees, an important development of the Skanda-Murukan tradition in the post-Chola period is the identification of Murgan as an object of intense personal devotion. The bhakti tradition draws from the philosophic as well as folk religious experience where, in the frenzy of intoxication, the worshipper felt himself to be possessed of the deity.

In the medieval period, Skanda-Murukan imbibed as many Sanskrit aspects of Subrahmanya as the Tamilness of Murukan. He is supposed to symbolise eternal youthfulness and Arunagirinathar's poetry Tiruppukal captures the essence of this eternity along with conscious detachment from things worldly that a Shaiva Siddhantin would quest for. His colourful invocation of the image of Murukan riding on a peacock as if rising like a sun above the horizon and metaphorical language identifying Murukan's qualities with a jewel and a flower are worth noting. A verse from the Kandar Anubhuti provides an example of the free use of Sanskrit and Tamil diction:41

Uruvay arulvay ulatay ilatay

Maruvay malaray maniyay oliyayk

Karuvay uyirayk katiyay vitiyay

Kuruvay varuvay arulvay kukane

Formed and formless, being and non-being

Flower and its fragrance, jewel and its luster

Embryo and its life, goal of existance and its way

Come, You, as the Guru, and bestow Your grace.

The devotional relationship envisioned by Saiva Siddhanta entails a complex series of stages to the ultimate relationship. This relationship with the God may take any of the following forms: master-servant, father-son, friend-friend, master-pupil, lover-beloved.42 For an ordinary devotee, the aspiration is as mundane as can be, but the faith is deep and unshaking. The present day devotion expressed by Murukan devotees bearing kavati is simple, they see him in many forms, some as bālaswāmi and some as sēnāni, some invoke Idumban while some imagine Murukan as glowing light.

Their emotions intensify as they reach the sanctum; some are unable to move forward as if dazed by disbelief, while some pass into a trance from which they are barely able to remember anything: a glimpse of the beloved deity is all they aspire to get. For some it is a purifying and elevating experience, for some it is extolling the benevolence of their beloved deity, for many it is simply seeking prosperity and longevity. Whichever way one looks at it, it is the abiding faith and endurance in ascetic ways which keeps the ordinary grihasthas engaged in Murukan devotion going.

Bibliography

- Fred W. Clothey. The Many Faces of Murukan: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God, (Mouton Publishers, 1978).

- S. Arasaratnam. Indians in Malaysia and Singapore, (London: Oxford UniversityPress, 1970).

- S. Arasaratnam. Indian Festivals in Malaya, (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya, 1966).

- Elizabeth Fuller Collins. Pierced by Murukan's Lance: Ritual, Power and Moral Redemption among Malaysian Hindus, (North Illinois University Press, 1997).

- Lawrence Babb. "Tai Pucam in Singapore: Religious individualism in a hierarchical culture", Sociology Working Paper No. 49, (Singapore: Chopmen Enterprises, 1976).

- Kamil Zwelebil. Tamil Traditions on Subrahmanya-Murugan, (Madras: Institute of Asian Studies, 1991).

- A. Palaniappan. "Arulmigu Thandayuthapani Temple", in Śrī Thandayudhpani Temple Kumbabishekam souvenir, (Singapore, 29.11.1996).

- Jean Pierre Mialaret. Hinduism in Singapore: A Guide to the Hindu Temples of Singapore, (Singapore: Asia Pacific Press, 1969).

- K.S. Sandhu and A.Mani (eds.). Indian Communities in South East Asia, (Singpore: Times Academic Press, 1993).

- George Abraham. "Indians in South-East Asia and the Singapore Experience" in Dr. Jagat K. Motwani et al. (eds.) Global Indian Diaspora: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, released as a commemorative volume at The Second Global Convention of People of Indian Origin, Global Organisation of People of Indian Origin, New York, 1993.

- Marian Aveling. "Ritual Change in the Hindu Temples of Penang", in T.N. Madan (ed.) Contributions to Indian Sociology (new series), Vol. 12, No.2, (University of Delhi: Institute of Economic Growth, 1978).

- Carl Vadivella Belle. "Tai Pucam in Malaysia: An Incipient Hindu Unity" presented at the First International Conference Seminar on Skanda-Murukan, Institute of Asian Studies, Chennai, 1998, http://murugan.org/research/belle.htm

- H.F. Pearson. Singapore: A Popular History, 1819-1960, (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1961).

- C.M. Turnbull. A History of Singapore 1819-1988, (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- M. K. Narayanan. Munnaal Thalaimagan Lee Kuan Yew, Singapur Varalaru 1819-1990, (Singapore: Raffles Publishers) translation of selected portions on Tamil/Indian Influence in the Ancient History of Singapore

- Oral History Accounts by Tamil- Speaking Indians from Communities of Singapore Part 2, (Singapore: Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore).

- Translations of Tamil Murasu articles by Vidya Nair from microfilm collection of the National Library, Singapore.

End Notes

1 The South Asian Department of the Asian Civilisations Museum has been involved in documenting the ancestral cultures of Singaporean Indians. One of the most obvious choices was to document Tai Pucam and Tīmiti, the most popular Hindu festivals practiced for almost 100 years in Singapore. Besides these, many other festivals such as Krishna Jayanti, kumbabhishekams and festivals especially connected with Murukan cult have been studied and documented by the team of curators including Gauri Krishnan, Chung May Khuen and photographer Kuet Ee Foo.

2 kavati is a horizontal pole lifted on the shoulder, either across the back or on either one of the shoulders, and supported by one arm. On either end of the pole two objects are tied, in the case of Murukan kavatis it is two pots of milk or brown sugar. Many street vendors carried their wares on such devices in parts of Asia and in many agriculturalist counties, freshly cut crops and water buckets are still carried by similar devices.

3 Nakkirar's Tirumurakārrupatai of 5th century is an important book of the Shaivite Nayanmars of Tamilnadu

4 After Fred Clothey, it is an all encompassing term to describe various aspects of the cult.

5 Fred W. Clothey, The Many Faces of Murukan: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God, 1978, p. 132.

6 ibid, p. 132, Paripatal 6:7-10.

7 Sanskrit āmāvasya or Tamil āmāvacai

8 Sanskrit Shashti

9 In Singapore, we documented the Skanda Sasti festival at the Muneeshwaran temple in Queensway area, during which an ubhayam was celebrated and an enactment of the killing of the demons was performed. An actual cockerel was brought in to the play with the puppet demon changing many masks.

10 Sanskrit paurnami

11 ibid, p. 132-136

12 ibid, p. 136

13 ibid, p. 137, and Champakalakshmi, 1968:91 from Clothey

14 Clothey, 1978: p. 137-138

15 Carl Vadivella Belle, "Tai Pucam in Malaysia: An Incipient Hindu Unity", presented at the First International Conference Seminar on Skanda-Murukan, Institute of Asian Studies, Chennai, 1998, http://murugan.org/research/belle.htm , p. 6

16 Clothey, 1978: p. 142

17 Ayyar 1921: 59, Clothey 1978: 142

18 Clothey 1978: 143

19 ibid, 147.

20 In Gujarati and Hindi referred to as kavad, although never seen being used for any religious purpose in northern India. Although traditionally there is a tale from the Ramayana in which a kavad is used by Shravankumar to carry his blind parents on a pilgrimage to many religious sites in India.

21 Carl Vadivelle Belle, op cit, 8

22 This interpretation was given to us by Mr. Andiappan, a Chettiar devotee from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia that carries kavati in Penang each year during Tai Pucam and has vowed to do it for life. From conversation in January, 2000.

23 Tīmiti is a festival of fire-walking celebrated in Singapore as part of a larger festival in honour of Draupadi and the Mahabharata characters. This festival is the next most popular of the Indian festivals celebrated in Singapore.

24 Vineeta Sinha, K.S. Sandhu and A.Mani (eds.) Indian Communities in South East Asia, Times Academic Press, 1993, p. 828

25 Sandhu 1969, Arasaratnam 1967, Sinha, in Mani and Sandhu, op.cit., 829

26 Nair, 1972

27 references, Tamil Murasu, Jan-Feb 1940

28 According to statistics provided by the Hindu Endowments Board in 1998, 8998 people carried palkudams, ordinary kavatis and alaku kavatis, which was 2.4% increase over 1997. Totally 583 people carried alaku kavatis, which is 7% increase since 1997.

29 Sinha, op.cit, 829

30 The Nattukottai Chettiars are a caste of moneylenders from Cettinad area in Tamil Nadu who have conducted business all over Southeast Asia since the late 18th century.

31 A. Palaniappan. "Arulmigu Thandayuthapani Temple", in Śrī Thendayudhpani Temple Kumbabishekam souvenir, (Singapore, 29.11.1996)

32 C.M. Turnbull

33 Palaniappan, op.cit, 29

34 George Abraham, "Indians in South-East Asia and the Singapore Experience" in Dr. Jagat K. Motwani et al. (eds.) Global Indian Diaspora: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, released as a commemorative volume at the Second Global Convention of People of Indian Origin, (New York: Global Organisation of People of Indian Origin, 1993) pp. 269-277

35 brochures Singapore Festivals, Tai Pucam,1993; Navarathiri, 1993; Thimithi, 1993; (Singapore Tourist Board: Singapore New Asia, Official Guide, 2001).

36 Documentation conducted by the South Asia Department in Singapore, Malacca and Penang during kavati festivals will be pubilshed in a few years time.

37 First mentioned in conversation by Dr. Tinappan, Senior Lecturer, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University and then reiterated by several Chettiar devotees who were interviewed.

38 Carl Vadivella Belle, op.cit, 8

39 Explained to me by a group of veteran devotees of the Kampong Bahru have inherited the Vaithi kavati and still carry the Janma kavati taken by Mr. Pakarisami with which the Kampong people associate their Kampong cameraderie. Some of the active informants of this group are Mr. Gopalsami, Mr. Jayabalan and Mr. Rajaram, whom I have interviewed several times in the past five years on different occasions in the context of Tai Pucam and Tīmiti.

40 According to my principal informant in Singapore, Mr. Jayabalan of the PSA group.

41 Clothey 1978: 111

42 Devasenapati, 1963: 8; Clothey 1978: 103

Gauri Parimoo Krishnan is a curator in charge of the South Asian collection at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. She has taught Indian and Western art history and aesthetics at M.S. University, Gujarat.

Contact the author:

Asian Civilisations Museum

National Heritage Board

Singapore

E-mail: gauri_krishnan@nhb.gov.sg