|

|||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

Cult of Skanda-Murukan in TamilakamThe antiquity of Murukan worship in Tamil Nadu

by Ambikai VelmuruguMurukan has been worshipped in Tamil Nadu for many centuries before Christ. The ancient Tamil people closely observed the beauty of nature and realised that there must be a Supreme Being to regulate the affairs of this world. Considering that the Supreme Being permeates every minute thing in this world, they named it as kantali. There is a reference to kantali in the Tolkāppiyam. In Tolkāppiyam Porulatikaram it is written: Kotinilai kantali valli These three devoid of blemishes occur with dignity with God's invocation.1 The commentator Naccinarkkiniyar says that kotinilai refers to the sun; kantali is the cause of creation and destruction of this universe, and therefore something that remains unattached, unaffected and formless being existing by itself and transcending all philosophy; while Valli denotes the moon. In later times Tamils considered the exuberance of beauty that surrounded and became visible all around the hilly tracts as the forms of God. The divine form that appeared in the hills appealed to the people so much that, considering the reddish hue and the exuberance of youth, they called him Cēyōn. Observing his handsomeness, youthfulness and sweet fragrance that emanated from Him, they spoke of him as muruku. These two names have been used profusely in Cankam literature.2 Among these names, the word muruka with the masculine ending an became Murukan. Later, when Tamil Nadu itself was divided into four tracts, Murukan was categorised as the presiding deity of the hilly tracts, the Kuriñci, the foremost of the four tracts. The antiquity of Murukan worship may be explained in another way too. During the Cankam period, the earliest forms of worship appear to be the practice of worshipping stones, implanted under shade trees. This form was called kantu. References to this kantu form of worship may be found in Tirumurukarruppataai and Pattinappālai.3 The Pattinappālai has pointed out that, in this form of worship the kantu (post) was decorated with flowers etc., and with lamps lighted. At the beginning, even Murukan Himself is seen to have had the right to kantu worship. We learn from Cankam works that the katampu tree (Anthocephalus katampu) is sacred to Murukan4 and, as a consequence, Murukan is honoured with the name Katampan.5 Excavations prove that tree worship was in vogue for centuries before Christ. Hence, it is clear that the katampu tree worship which existed among the early Tamils also suggests the antiquity of the worship of Murukan. Further, in the Baudhayana Dharma Sutra, names such as Skanda, Sanatkumāra, Vis×āka, Sanmukha, Mahasenā and Subrahmanya, etc., have been attribued as names of this same deity. The Baudhayana Dharma Sutra is regarded as belonging to the period prior to the 4th century BC. That the name Subrahmanya was widely used in South India is vouchsafed by this work.6 Thus, we may conclude that the worship of Skanda-Murukan was in practice all over India even prior to the 4th Century BC. During the Neolithic Age (the period between the 3rd century BC and the middle of the first century AD), the practice of interning the bodies of the dead in containers or urns turned out of stone before burial was common in Tamil Nadu. Urns of this type, circular in shape, have been found in large numbers in Adhichcha Nallur in the Tinnevelly district of Tamil Nadu. Some research scholars consider the urns of this type as being pre-Neolithic. Evidences are now available from these urns that suggest that the people who belonged to the Adichcha Nallur civilization practiced the worship of Murukan. Murukan had the cock on his banner and the spear as his weapon. In Adichcha Nallur spears made of iron and metal tablets with the cock as insignia have been unearthed.7 Considering all this, we may surmise that Murukan worship originates from a period many centuries before Christ. Ancient Tamil literary works establish beyond doubt that certain emblems, marks of identity, and places of worship belonged exclusively to Lord Murukan.

Kārttikeya worship in North IndiaArchaeological relics and literary works suggest that the worship of Kumāra gained prestige from very early times in North India. The holy name of Murukan is talked about widely in Tamil Nadu. In North India, the god is known by such names as Kumāra, Swāmi, Mahasena, Skanda, Kārttikeya, Guha, etc. Skanda worship must have taken its origin in North India from pre-Vedic times. During Vedic times, Skanda was associated with Agni. In the Atharva Veda, Skanda is described as Agnibhu, the son of Agni. In the Sathapata Brahmana, Skanda is portrayed as the son of Rudra. In the Chandogyopanishad, when once the sage Narada was depressed in mind and suffering mentally, he met sage Sanatkumāra, who told Narada that Skanda is He who gives efficient light and divine wisdom. In the epics Rāmāyana and Mahābhārata too, the story of the birth of Skanda, the destruction of the demon Tāraka, the blasting of the mountain Krauñca and other stories are narrated elaborately. In the Rāmāyana Bālakanda, when Rama requests the sage Kausika to relate the story of the river Ganges and the birth of Skanda, the learned Kausika described the birth of Skanda in detail.8 In the Mahābhārata Salliya Parvam, when Janameja inquires from Vaisambhayana about the birth of Skanda, Vaisambhayana obliges.9 In Sanskrit purānic literature, in the Maccapurāna, Padmapurāna, Mārkkandēyapurāna and Vāyupurāna, abundant references Skanda may be found.

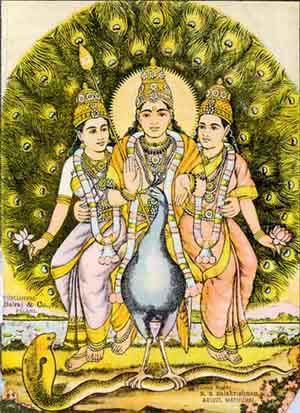

There is also evidence that many kings and emperors of North India worshipped Lord Skanda. On coins minted during the time of Kushan ruler Kuviska, the emblem of Kārttikeya was superimposed. Similarly the Yaudheyas also had their insignia of Kārttikeya with his vehicle the peacock inscribed on their coins. In some silver coins of the Yaushadars the form of Kārttikeya with six heads have been impressed. Kumāra Gupta I, the first of the Gupta dynasty, is known to have been very much devoted to Kārttikeya. Kumāra, by which name he was known, and Skanda, the name of his son, confirm not only the fact that the Guptas were the votaries of Kārttikeya, but also the reputation and popularity these two names enjoyed during the Gupta period. Further, on some Gupta coins, the image of the peacock had been inscribed. Therefore, it is quite clear that Gupta monarchs gave importance to Kārttikeya. Mahākavi Kālidāsa composed the popular literary work, the Kumārasambhava, in which he described the birth of Kumāra in beautiful verse. At the time Kārttikeya worship was developing in North India as a religious cult, simultancously in South India Murukan worship was flourishing. When the Christian era dawned, North Indian traditions migrated to the South and became integrated with Murukan worship, producing a synthetic cult with many special features and with aspects exclusively belonging to Murukan. Murukan worship in ancient Tamil literatureMany works in Tamil literature extol the birth, prestige and divine grace of Lord Murukan. Such Cankam works as the Ettutokai, Pattuppāttu and Tolkāppiyam are replete with information about Murukan worship. Among are noteworthy works. Ettutokai and Paripātal belong to earlier periods. In the Ettutokai, Pattuppāttu, Tirumurukārruppatai and Paripātal, descriptions of rural social conditions include brief notes of Murukan worship. It is relevant to consider at this stage the background of social conditions and the special features of Murukan worship that prevailed among people of Tamil Nadu as told in these works. In Tolkāppiyam there is a statement that speaks of 'the blue mountainous world with Cēyōn/ presiding'.10 Here Cēyōn refers to Murukan. Thus Murukan was hailed as the unique presiding deity of the Kuriñci tract, the hill and hilly regions. It was believed that wherever there were hills and mountains, there Murukan took his abode. This is the reason why Murukan was also known as the Lord of Hills, kunrak kilavan meaning the Lord of the Hills. In the section Kunrutōratal in the Tirumurukārruppatai, another poet Nakkīrar sings that on every hill, Murukan may be seen in a dancing costume (198-217). Though Murukan was considered as the prestigious deity belonging to the Kuriñci tract, the ancient Tamils worshipped Murukan without any distinction of region and tract whatsoever, as is elaborated in the Tirumurukārruppatai and other works. Poet Nakkīrar observed the following additional places where Murukan resides: viz. the stage where Vēlan performs the dance dedicated to Murukan, forests, parks, groves, and deltas in the midst of flowing rivers and tanks (lines 218-226). In the invocatory verse in the Kuruntokai, another Cankam work, Murukan is described as the Lord of the entire universe. That verse concludes with the note that the whole cosmos is under his care and protection.11 The beautiful sight of Murukan, the Lord of the hilly tract seated in the littoral tract and playing and celebrating festivals is vividly sung in the following Pattinappalai verse:

Clasped with palms of hands

Therefore it is quite clear that the early Tamil people engaged themselves in the worship of Murukan without distinctions among all the various landscapes. In ancient Tamil literary works, the two names Cevvēl and Cēyōn were widely used to denote Murukan. The Cēyōn of Tolkāppiyam is the Cēy of Paripātal. Cēy means `son' `yonder' and `red complexion'. These literary works regard Murukan as a god with fair complexion and honour him with the name Cēy. Paripātal refers to Murukan by the name Cevvēl. Vēl denotes Manmatan, the god of love. It also means `masculine valour'. Therefore the name Cēvvēl refers to Murukan as an ideal fair, valourous and vigorous young man. The ancient Tamils saw in the rising morning sun and the setting evening sun, the splendour and glory of its red rays as they beat on the slopes of hills and lost themselves in ecstasy. Through that scenic beauty, they visualised Murukan coming on the back of his vehicle, the flying peacock. That is the reason for them to have worshipped him as Cēvvāl. In many ancient Tamil literary works, the rising of the morning sun with its fiery red rays was compared to Murukan or Cēyōn. In the Tirumurukārruppatai, Nakkīrar compares the enchanting form of Murukan to the reddish sun and praises him as the unfolding of the flame.12 That Nakkīrar conceived Murukan of his intense prayers as the supreme godhead is borne by this statement. In Paripātal, the body of Cēvvēl is compared to the sun's radiant light and referred to as the hue of the sun's chariot in the form of fire. Further, in Paripātal the sun's halo is compared to the six heads of Lord Murukan (stanza 5 line 10). In ancient Tamil literature, the dance called Vēlan veriyāttu or Kuravai kūttu has earned great reputation in connection with Murukan worship. The major occupation of the male inhabitants of the Kuriñci (hilly tract) was hunting. They used the spear as their most important weapon. They placed this spear that protected their lives in the hands of Lord Murukan. By this act, Murukan (who wielded the Vēl or spear) became to be known as Vēlan. As time passed, the shaman-priest who performed pujas to Murukan also came to be known by the same name vēlan. People who were afflicted with misfortunes and calamities presumed they were caused by Murukan Himself and sought oracular remedies from the vēlan. At that time the vēlan would be mesmerized and would commence to dance. This dance was called `vēlan's mesmerized dance' (Vēlan veriyāttu). Explanations and references to this may be found in such works as Kuruntokai, Akanānūru and Narrinai.13 About the worship of Murukan, Akanānūru says that the dancing arena should be constructed according to specifications. On it the Vēl (spear) should be installed and properly decorated with flowers and garlands. The praise of Vēlan should be sung so that a medley of noises is created in the sacred precincts. Sacrificial offerings are made to Vēlan, with white oats moistened in red blood and sprinkled all over. Thus worshipping Lord Murukan, Kuruntokai mentions that the white heated oats were strewn over the entire arena when the dance was recited. The Cankam work Narrinai mentions that the vēlan is adorned with the garland of fragrant katampa flowers that are in full bloom during the rainy season, and stands invoking Murukan's blessings. Murukan would descend upon the arena of those frenzied dances only to accept the consecrated sacrificial offerings. In Tirumurukārruppatai it is mentioned that women from the mountain tracts performed veriyāttu dance. Tirumurukārruppatai further eulogizes the mountain damsel who performs the worship. She would hoist the cock-flag, gleaming to it white mustard with ghee, sprinkle flowers and fried rice (pori), fill bamboo baskets with white rice soaked in the blood of sheep, apply sandalwood paste, and hang garlands of alari flowers around the arena. Then she would bestow blessings on the various villages, blow sweet-smelling incense fumes and sing Kuriñci tunes. At this time, variegated musical instruments would play in chorus. Then she would pray to Lord Murukan to come down to the arena. When the Kuravar people thus worship Murukan, He gladly accepts their worship and grants them their prayers (Tirum. lines 227-249). There are also references in Cilappatikāram canto Kunrakkuravai to this veriyāttu dance. Cilappatikāram canto Kunrakkuravai speaks of a mother who, not being aware of her daughter's lovelorn behaviour and suspecting Murukan himself has seduced her, gets the help of a vēlan to have the veriyattu dance performed. The kuravai kūttu is intimately connected to the worship of Murukan. In the mullai (forest tract) shepherdesses dance the kuravai for Lord Murukan. In the mountainous tract, the hill-tribes perform the kunrakkuravai for Lord Murukan. Kuravai kūttu is performed by seven, eight or nine maidens moving in a circle while holding each other's hands with fingers inter-looked, dancing to the rhythm of music. The Malaipatu-katām of Pattupāttu collection mentions (line 320-322) that the natives living in the hills, who had taken cups of intoxicants in the morning, join hands with their wives, beat the small drums (ciruparai) made of deerskin, and danced the kuravai at the summit of hills. If any misfortune befalls them, the vēlan shaman-priests would tell the people that it was the effect of Murukan's wrath. To remove that misfortune the vēlan would decorate himself with garlands of kuriñci flowers and, sporting the spear in his hand, would enshrine Murukan in his body and perform the worship. Maturaikkanci mentions (lines 611-615) that at the same time damsels would perform the kuravai kūttu in the various theatres. The Maturaikanci also says (lines 96-97) the maritime (neytal) women also were in the practice of dancing the kuravai in the littoral districts. Nakkīrar, in the Tirumurukārruppatai Kunrutoratal gives in detail particulars relating to kuravai kūttu. The Veddahs (vetuvar) loudly play the tontakam, parai, etc. as they dance the kuravai kūttu. The veriyātum vēlan shaman-priest weaves the takkolam (unripe fruits) the mallikai (jasmine) and ventalai flowers with green creepers into a garland and adorns his head with it. Damsels also dance the kuravai kūttu, inter-weaving into their plaits festive garlands wreathed with fragrant flowers. They wear round their waists costumes that are woven with cool green foliage. The vēlan shaman-priest too sings and dances with these dancing damsels (lines 190-217) as related in the Tirumurukārruppatai. In the Cilappatikaram canto 24 entitled Kunrakkuravai, Murukan worship is extolled in a variety of forms. This canto gives us a description of a combination of subjective poetry and invocatory prayers. After destroying the city of Madura, Kannaki arrives at Tirucenkodu. There she remains at the base of the trunk of a neem (vēnkai) tree in full bloom. As the guardian deity of Madurai predicted, fourteen days had elapsed since Kovalan died. When Kovalan descended from heavens high up, upon the earth below, Kannaki accompanies him in his air-borne vehicle heading towards heaven. The men and women of these hilly tracts, having seen the flight of the couple, perform the kunrakkuravai dance for the benefit of Kannaki. In this kunrakkuravai, they sing praising the paramountcy of her greatness. Further they sang other songs associated with Murukan. Thus, through vēlan's dance of veriyattu and kuravai kūttu, the reputation and popularity enjoyed by Murukan worship among the village folk is quite evident. Certain ancient Tamil works associate Murukan worship with the tunankai dance. In Tirumurukārruppatai the victory by Murukan over his enemies Cūrapathman and his demon hordes is mentioned. When Cūran and his demon soldiers were vanquished, a she-devil (pēymakal) relishes eating the flesh from the heaps of the corpses of the demons. The Tirumurukārruppatai (lines 45-56) describes in great detail this devil with parched hair, irregular rows of teeth, reddish eyes of anger, stomach with rough skin, ferocious gait, who swallows the flesh in the battlefield where Cūran was defeated and feels ecstatic over the sumptuous meal she enjoys, extoling the exploits of Murukan and the battlefield and dancing the tunankai kūttu.14 The sixth and eighth stanzas of Nallantuvanar's Paripātal refers to the swearing of oaths on Murukan in petty squabbles among small families over trifles. In the eighth stanza the maid addresses the hero (to be husband) in these words (lines 65-66): 'Have mercy on me. If you violate the oath taken by you in the presence and in front of Murukan whom you adore, the sharp spear of the God will consume you.' From this statement it is clear that a dreaded reliance was prevalent among the ancient Tamils who believed that if they made a false oath a great calamity would befall them. The eighth stanza of Paripātal (lines 103-108) relates how maidens, including young girls, yearn to get good husbands, and how wives of those husbands who went to far off to distant lands in search of wealth, long for them to return home quickly and safely and how married women who long to conceive, all engage in many forms of prayers and worship. The ancient supreme God Murukan of the Tamils became associated with the North Indian counterpart Kārttikeya during the latter part of the age of the ancient Tamils. The Tirumurukārruppatai, Paripātal and Cilappatikāram bear ample testmony to this view. Lord Murukan makes his glorious appearance for the first time as a six-headed god in the Tirucciralaivāy section of the Tirumurukārruppatai. Nakkīrar explains the significance and functions of his six heads in order. Of the six faces of Lord Murukan: one illumines the cosmos enveloped in darkness; one face approaches his devotees, listens to their maladies and grants them boons; one face showers welfare measures of the Vedic rituals of holy Brahmins; one face imparts the knowledge of reality and like the moon, casts light on the directions; one face with determination, will and anger destroys foes and makes a battlefield of oblations; and one face rejoices the companions of Valli, the daughter of the hillman (kuravan). Thus Nakkīrar describes the divine grace of the six faces (lines 83-103). In Paripātal and Cilappatikaram also Murukan is depicted as a superb god with six faces.17 At this stage, the North Indian tradition became integrated with South Indian mode of Murukan worship. Murukan made his appearance with his six graceful faces, and the residents of kuriñci (hilly tracts) attributed all their belongings to Murukan and placed them in his twelve hands, viz. the spear (vēl), the sword (vāl), the javelin (itti), the pick axe (kōtali), the goat, the peacock, the deer and the other symbols for him to wield and use freely. They sang the glory of the twelve shoulders comparing them to the musical instrument mulavu of the hunting tribes. They attributed the scars of wounds that were inflicted with in their battles to Lord Murukan and sang in praise of the scars of victory strewn all over his body. They made as his vehicle the elephant, the biggest animal of their region. They gave Valli, the daughter of the mountain chief, in marriage to Him. They sprinkled and spread in his front as a form of veneration, fragrant and lovely flowers like kuriñci (Gloriosa superba), kantal, katampu and vetci which grow abundantly in the hills. They offered Murukann honey (tēn), milet (tinai), and blood of goats, etc. In this manner the residents of the central hills view Murukan through the products of daily use, combining North Indian and South Indian traditions. The Tirumurukārruppatai, Paripātal and Cilappatikaram, in explaining the birth of Murukan, follow the Sanskrit literary versions. On this basis, Tirumurukārruppatai praises his birth as the Holy Child brought up by the six Krttikā maidens as the Son of God, the Son of Palaiyol wearing beautiful jewels, the Son of the Goddess of the big mountains, and the Commander of the Army of the Gods, etc. Even the eighth stanza gives the birth of Cevvēl with minor sporadic variations. In Cilappatikāram the birth is explained as that of Him who sucked milk from the breasts of the mothers who were in the holy and beautiful Saravana Poykai (pond of reeds) and the one who wields the lance with his hands (Kunrakkuravai - 10). Further in all three works we find Murukan being associated with Lord Civan. We find references to Him as the Son of God seated beneath the banyan tree, in Tirumurukārruppatai (line 258) as born as a moon to the Blue Throated God in Paripātal (line 7) and as the Son of God of the Banyan tree in Cilappatikāram (Kunrakkuravai 13-15).

As a result of North Indian influence upon the South Indian tradition, Tamil literary works made Valli the consort of Murukan and Devasenā (Teyvayānai) the queen of North Indian Kārttikeya. His first consort Teyvayānai is regarded as Indira's daughter and of northern origin, whereas his second consort is considered as the Child of the Soil of Tamil Nadu and daughter of the kuravar chief. In the ninth stanza of Paripātal, Nallantuvanar contends that Murukan fell in love with Valli and married her, that Teyvayānai hearing this got angry and wept and, losing her temper, entered into a feud with Valli, thus giving a touch of humour and imagination. As Valli and Teyvayānai had a squabble between them, their peacocks quarreled; the parrots antagonized each other; the honey bees clashed; the maids of both confronted each other; and finally Valli came out victorious. Kamil V. Zvelebil, who made an in-depth study of this stanza, says, "This squabble took place between Valli, who belonged to the indigenous Tamil soil, and Teyvayānai who came from a foreign soil. This shows a conflict between two opposing cultures and also reveals a clash between Tamil and Sanskrit languages; this demonstrates the war between the secret love (clandestine union between lovers) and open marriages (conjugal fidelity), between love and lust between lovers."18 During this period we also see the amalgamation of the Murukan worship procedures of vēlan veriyāttu and kunrakkuravai, which are special to the Tamils, and the Vedic principles and the elevation of Murukan worship to higher state. These characteristics assumes prominence in the Tiruverakam section of Tirumurukārruppatai. Brahmins of high birth and ancestry who have excelled in their habits and manners are at Tiruverakam. These Brahmins who are competent in the four Vedas and have observed celibacy for 48 years, are worshipping Murukan with mantras from the Vedas and singing devotional hymns. The Tirumurukārruppatai says that they utter the sadāksaram (the six-syllable mantra) and sprinkle fragrant flowers as they pray. This makes Murukan overjoyed and makes him take his residence at Tiruverakan (lines 177-189). In the Palamutircolai section, Murukan is praised as the wealth of the Brahmins (line 263). The Paripātal (verse 14; line 27-28) praises Murukan as possessing unique fame. Therefore, it is clear that in later periods, Vedic beliefs were integrated with Murukan worship. As a result of this change, vēlan veriyāttu and kunrakkuravai etc. that were in vogue among the Tamils had, by the passage of time, gone out of practice. In Cilappatikaram the damsels engaged in kunrakkuravai dances. At the same time, in Cilappatikaram Katalatukatai canto, Ilankovatikal introduces the tuti and kutai as dances (kūttu) that praise folk.19 These dances appear to belong to the tradition of royalty. Ilankovatiakal says Murukan annihilated Cūran's powers, which challenged him. He uses the waves of the mid-ocean as the theatre, performs the tuti kūttu and makes the asuras suffer and, after downing their weapons, holds the umbrella in front and performs the kutai kūttu. So, we see in Cilappatikaram, how the folk dances of vēlan veriyattu and kunrakkuravai are made subjects of ridicule when they are compared with prestigious Vedic forms of Kaumara worship; and we observe how royal forms of worship are introduced. We also observe how later the Vaisnava poet-saint Nammalvar lashed at the folk-dances, when he said when the food is rotting, what is the earthly use of the movement of the jaws?20 As the varied forms of veriyāttu dances etc. fail to obtain the prestige of Vedic forms of worship, in course of time they declined and disappeared. Further, we are inclined to believe that, along with the development of Vedic forms of worship of Murukan, temples for His worship could have gained custom and popularity. Tirumurukārruppatai mentions the six places, Tirupparankunram, Tirucciralavay, Tiruvavinankuti (Palani), Tiruverakam, Kunrutorādal and Palamutircolai. The beginning of Murukan worship, which had the worship of spears stuck in places beneath the trees, was known as kantu worship. In Cilappatikaram canto nine, there is a reference to the spear being worshipped, rather than the worship of a statue of Murukan. The Brahmin woman Malati carrying her departed son on her shoulders is reported to have been visiting the temples one after the other in turn; in the course of this mission she is mentioned as having gone to the temple of Vēl (Kanatiram Uraita Katai, line 11). This proves that there was in existence a temple exclusively for the worship of Murukan and that Murukan worship was very widespread and prevalent in Tamil Nadu. Thus, there appears in Tamil Nadu the practice of constructing separate temples for Murukan worship, along with the advancement in Vedic worship. Murukan, who had been roaming about and dancing on the hills, came to the waves of the oceans and took residence in the temple in the ocean. Akananuru verse 266 sings of this scenic beauty as the son Cēy occupying the abode in the waves likened to a bright lamp. Purananuru describes the splendour of Murukan adoring the Tiruchendur temple as follows: 'In Centil where the ocean waters with white foam rock and roll, there you find the beautiful harbour with the great Vēl stuck' (Puram 55). The six holy places of Murukan described in Tirumurukārruppatai are now referred to as six military camps (patai vĪtukal). Tirupparankunram is praised in Paripātal and Cilappatikaram. All these show the growth of Vedic forms of Murukan worship in the midst of the ancient Tamils of later times. Murukann worship during the Pallava periodThis period that is glorified as the period of religious movements in Indian history, especially South India history, saw many changes in the religious organizations. In Tamil Nadu in the Christian era, North Indian influence began to infiltrate. Religious such as Buddhism, Jainism and Brahminical Hinduism and modes of worship like Saivism and Vaisnavam, and literary works like the epics, and purānas commanded considerable influence. Stories from the purānas became popular in Tamil folklore through educational institutions. These gathered momentum during the period of the Pallavas. As a result of the influence wielded by Saivaism and Vaisnavism during the Pallava period, Murukan worship, which the ancient Tamils cherished in its pristine glory, was absorbed by Saiva religion. During this period, the Murukan temple at Tirupparankunram was converted into a Sivan temple. Tiruñānacampantar and Cuntarar considered Tirupparankunram as a place of Siva worship, and separately sang hymns in honour of Siva. Even Tirunavukkaracu Nayanar adores Sivan there and sings in praise of this, as a God almighty resides the shrine Tirupparankunram, where devotees sing and dance. In the hymns of the Saiva saints, Murukan is viewed as one connected with Siva. Campantar sings of Siva as the Father of Kumaravēl21, Father of Kumaran22, The Father of Cuvāmi23, Father of the rider of the peacock vehicle24, the Father of Murukan the Great25 etc. Like this, Cuntarar sings of Murukan as the one who destroyed Cūran in the ocean26, the Father of Him, who caused oceans to go dry27, the Father of Centan28, Father of the peacock mount Murukavēl29 etc. Saint Manikkavācakar praises Civan as Father of Kumaran30, Father of Vēlan the God,31 etc. We see abundant references to Murukan in the hymns of the first three Saiva acharyas. Manikkavacakar's hymns, however, are fewer. Among the holy names of Murukan are Arumukan, Kumaran, Centan, Maintan, Vēl, Mayirti, Murukan, Vēlan, etc. Among the holy names of Murukan, Cuntarar and Tirunavukkaracu Nayanar use the names Cettiyappan32 and Saravanan33 respectively for the first time in their hymns. In Campantar's hymns may be seen references to the creation of Murukan by Lord Siva to annihilate the enemies of the devas. Campantar sings of the Lord who created the young Kumaran34, He who eliminated the hostility of the devas by creating Cēntan35 and who blessed Arumukan to be born.36 The victory of Murukan over Cūran is exolled in many places. Campantar sings of the Father of Him who cut the deceitful Cūran.37 Cuntarar praises Him as Cettiyappan who defeated the Cūran who rose out of the ocean,38 Learned Reality, and as Murukan who fought and destroyed the demon Tārakan, who is addicted to intoxicants and alcoholic drinks39, He who enraged the great ocean,40 etc. The first three saints have, in many places, referred to the Vēl weapon, the cock, the banner, and the peacock mount. Cuntarar has swung an irony. Though the Son of God Civan, Murukan has married the daughter of a Kuravan, a tribal leader from the mountains40, genuinely intending to praise him, but has apparently demeaned Him. End Notes

Ambikai Velumurugu |