|

||||

|

| ||||

|

|

Patrick Harrigan as a Buddhist upasaka in Ceylon, 1971 |

However, my choice of journeying to Ceylon to follow my conventional notion of a spiritual life had unforeseen results. For as soon as I heard of Kathirkāmam or Kataragama, a jungle shrine sacred to the island's Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, and indigenous Vedda folk alike, I knew that I had to visit and see this remarkable place for myself. It would change my life.

A friend, a visiting American Buddhist, accompanied me to Kataragama where we stayed in a traditional yogāśramam, bathed in the waters of the Manikka Gangai, and approached Lord Kataragama Skanda's modest shrine with our offering of fruits, flowers and incense.

Kataragama has a well established reputation as a place where wishes are granted. So every pilgrim comes with a wish or an unsolved problem: students may ask to pass their examinations; others ask for resolutions to family problems; many come seeking to be cured of disease; while others come here hoping to get employed abroad.

Hearing that all these pilgrims were making a wish in exchange for their simple offerings, I resolved that I too ought to ask for something; after all, I had come from farther away than anyone. All I could think of was to ask the Kataragama God to find work for me also, any work. Without knowing it, simply by imitating the intentions and ritual actions of others, I had set in motion an unforeseeable chain of events.

My American Buddhist friend also described a peculiar European hermit who had been residing in Ceylon for decades, whom my friend was planning to revisit. I decided to accompany him and meet this 'German Swami' of Jaffna. This was yet another fateful step for me, for after barely meeting him I would soon recognize German Swami Gauribāla as my spiritual guide.

|

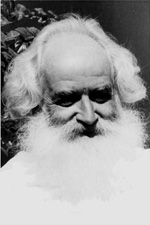

German Swami Gauribāla |

Swami Gauribāla Giri, although a cultured European, was not at all like modern swamis who yearn to have followers. Swami had already lived for 35 years as a homeless recluse from Ceylon to the Himalayas, much of that time under the stern tutelage of his mentor, the renowned sage Yoga Swami of Nallūr, whose indelible stamp remained upon Swami Gauribāla and many other ardent followers.

German Swami routinely shooed, shocked, or otherwise chased would be disciples away, such that few could remain for more than a few days, or weeks, or sometimes minutes only. After a few trials, Swami allowed me to stay at his ashram 'Summāsthān'. Despite being thrown out again and again, I always came back for more, from that day until Swami passed away in 1984.

In this traditional setting, I served my teacher by tending the ashram, listening to his spontaneous discourses, studying, and accompanying him on daily walks. I was willingly submitting myself unwittingly to an age old discipline: the traditional guru-disciple relationship designed to hammer and crack the eggshell of the disciple's ego consisting of his or her hardened opinions, the likes and dislikes that also define and delimit him or her. And in the bargain, I also imbibed the spirit of bhakti and sevā or thoṇḍu ('service').

Like Yoga Swami before him, German Swami used to perform pāda yātrā from Jaffna to Kataragama, a two month walk barefoot, annually with only the barest essentials tied in a tiny bundle, starting from the late 1940's consecutively for 25 years until the early 1970's when I accompanied him. In fact, his first ashram was in Kataragama and only later did he shift to Jaffna where he built his ashram to be near the 'Annādana Murugan' of Selva Sannidhi Murugan Temple, where daily offerings of annādanam (cooked food offered to the Deity and His devotees) keep hundreds of poor devotees