|

|||||||||

|

| |||||||||

Murugan and Valli

Part Two of a three-part series by Kamil V. Zvelebilfrom Tiru Murugan (Madras: International Institute of Tamil Studies, 1981) p. 40-46

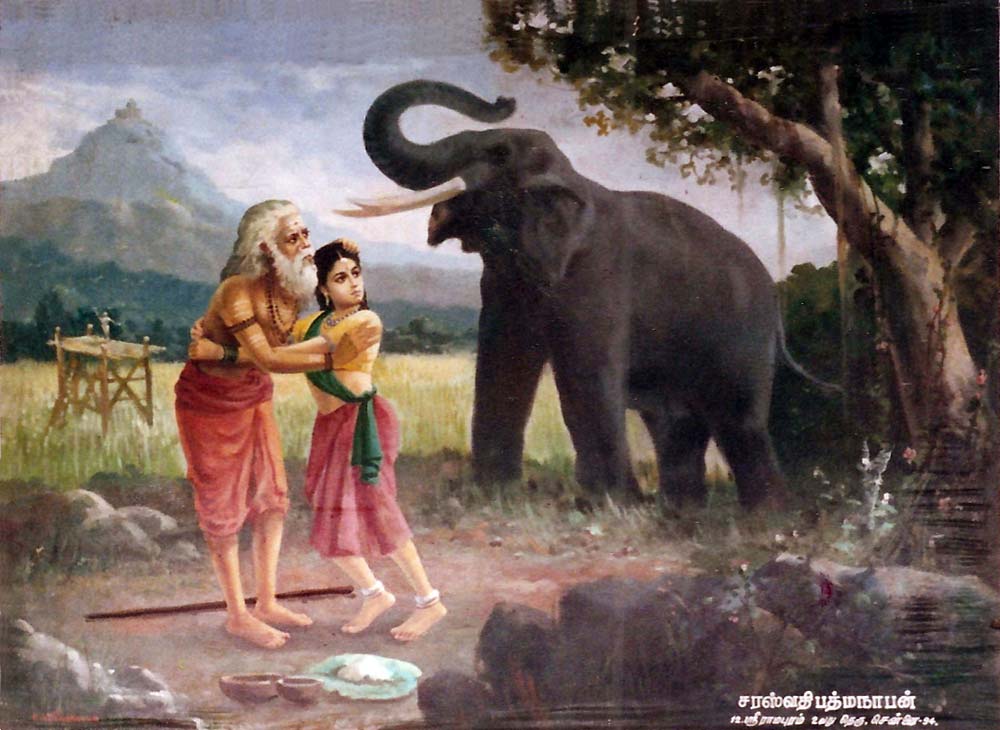

The old man asked Valli for food, and she gave him some millet flour mixed with honey. Then she took him to a small forest pond, where she quenched his thirst from the palms of her hands. Then he told her, "Now that you have satisfied my hunger and my thirst, do satisfy my love for you." Valli reproached him, and wanted to return to her field. At that moment, Murugan invoked the help of his brother Vināyaka who appeared behind Valli in the shape of a frightening elephant. The terror-stricken girl rushed into the arms of the Saiva ascetic for protection; he dragged her into a thicket and while embracing her revealed his real form, with six heads, twelve arms, and seated on his peacock. Carried away by this vision of her favourite god, Valli worshipped him and he told her that she was, in fact, the daughter of Tirumal. Valli complied with his wish, and they loved each other. A female companion of Valli questioned the girl about her absence and the striking change in her appearance, but Valli answered evasively. Soon after that, Murugan, again in the shape of a hunter, appeared in front of the two girls, and the companion observed that Valli and the hunter exchanged amorous looks. Therefore, she demanded that the hunter remove himself. He then admitted his love for Valli and he warned the companion that, if she would not help them to meet and enjoy their love, he would resort to the old custom of matal or riding the toy-horse in the village itself. The companion agreed to Murugan's request. As the harvesting time approached, the tribesmen called Valli back to the hamlet and the lovemaking was over. With a heavy heart she returned to the house of Nampi. Her clandestine love affair (kalavu) with the god ended. Her mother noticed Valli's unhappiness and invited soothsaying women who stated that Valli was possessed by the cūr of the slopes and that a ceremony in honour of god Murugan should be organized. Murugan went to the millet field and, not finding Valli there, he came, at midnight, to the hamlet, and with the aid of her companion, Valli and her divine lover eloped. Next morning Nambi's wife discovered Valli's disappearance. The furious hunter-chief organized a party of hillmen in pursuit of the fugitives. When they reached them, they discharged their arrows at Murugan, but the divine cock of the god crowed and the hunters fell dead. Valli lamented their death, but Murugan took her along. On their way they met Narada who explained to Murugan that he should have obtained the consent of the parents. The god therefore returned and ordered Valli to resuscitate the hunters which she gladly did. Murugan then assumed his true divine shape. Amazed and awed, the hunters worshipped him and begged him to return to the hamlet to be married in accordance with the custom of the tribe. The whole village rejoiced. The young pair was seated on a tiger-skin. What is so very thrilling in this story is the fact that almost step by step its structural slots and their fillers are derived from elements of the oldest Tamil tradition. It is the classical Sangam age all over: the heroine born among the hillmen; at the age of twelve, sent to guard the millet field sitting in the paran; the appearance of the god -- i.e. the talaivan, the hero, and his attempts at immediate, clandestine love-making (kalavu); the role of the toli -- the companion of the heroine; the motif of riding the matal-horse; the kaamanoy -- love sickness of Valli due to separation; the soothesaying women, and the veri dance of the velan, arranged to appease Murugan and dispell cūr; the motif of elopment of lovers. It is quite obvious that this story is purely and totally Tamil. I share fully the view that religious phenomena can be best understood on their own plane of reference, that they deserve to be interpreted in religious terms, and that the most fruitful approach to the study of a deity and its myths should be phenomenological and structural: an attempt to apprehend a vision of reality that persists throughout the history of a deity. However, any religious phenomenon is also a psychological, social, and historical phenomenon. A historical-evolutionary study, even a historical-evolutionary interpretation of a deity and its myths is necessary, too, at least at some preliminary stage of its investigation. |

Nampi placed the hand of Valli into the hand of Murugan and declared them married while Nārada assisted. At that moment, the gods appeared in the air and blessed everyone. Nampi then offered a feast - plenty of honey, millet flour and jungle fruits. After a short stay at

Nampi placed the hand of Valli into the hand of Murugan and declared them married while Nārada assisted. At that moment, the gods appeared in the air and blessed everyone. Nampi then offered a feast - plenty of honey, millet flour and jungle fruits. After a short stay at