|

|||||||

|

| |||||||

Murugan and Valliby Kamil V. Zvelebilfrom Tiru Murugan (Madras: International Institute of Tamil Studies, 1981) p. 40-46The story of Murugan's courtship and his union with the daughter of the hunters, Valli, is the most important of all Tamil myths of the second marriage of a god. In the Sanskrit tradition, Skanda is either an eternal brahmacārin (bachelor) or the husband of a rather colourless deity, Devasena, the Army of the Gods. In Tamil, in contrast, the earliest reference to a bride of Murugan is to Valli and there can be no doubt whatsoever that Valli is the more popular and more important of Murugan's two brides. Hence, I do regard the lovely myth of Murugan and Valli as an indigenous-autochthonous myth, a Dravidian myth; it also contains some of the oldest indigenous fragments of myth to survive, and some of the most ancient conceptual and ideological apparatus of the Tamils. The standard version, considered by Tamil devotees of Murugan as canonical and definitive (although not the only one current!), is found as the very last (24th) canto of the sixth book of Kacciyappa's Kantapuranam (composed around 1350 AD in Kanchipuram); entitled Valliyammai tirumanappasalam, it has 267 stanzas. Here is its brief summary: There is a mountain called Valli Malai or Valli Verpu, not far from the village of Merpati, in the Tontainatu country. In a village beneath the hill lived a hunter called Nampi; all his children being boys, he longed for a little girl. On the mountain slope, an ascetic by name of Śivamuni was engaged in austerities. One day a gazelle went by, and the ascetic was aroused by its lovely shape; his lascivious thoughts made the gazelle pregnant. The daughter of Mal incarnated in the embryo. In due time, the gazelle gave birth to a girl in a pit dug out by the women of the hunter-tribe when they searched for the tubers of edible yam (valli). The female deer, having round out that she had given birth to a strange being, abandoned the child which was discovered by the hunter-chief Nampi and his wife. Overwhelmed with joy, they took the little girl to their hut and named her Valli.

When Valli reached the age of twelve, she was sent to the millet field - in agreement with the custom of the hillmen – to guard the crop against parrots and other birds, sitting in an elevated platform called itanam (paran), and chasing the birds and other beasts away. The sage Narada, who visited Valli-malai and saw the girl, went to Tanikai to informed god Murugan about Valli's exceptional beauty and her devotion to the god of the hunters. Murugan assumed the form of a hunter and, as soon as he arrived at Valli's field, he addressed the lovely girl enquiring after her home and family. However, at that moment Nampi and his hunters brought some food for Valli (honey, millet flour, valli roots, mangoes, milk of the wild cow) and Murugan assumed the form of a tree (venkai, Pterocarpus bilobus).

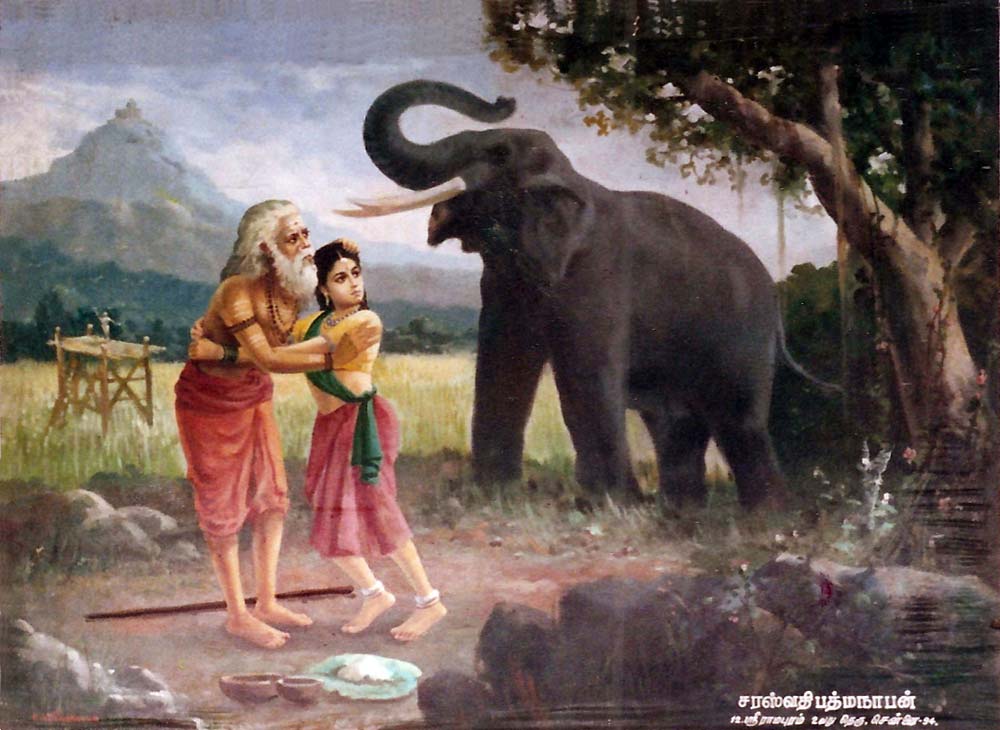

When Nampi and his company disappeared, the god reappeared in human form, approached Valli and told her that he would like to love her. Valli was shocked, lowered her head, and answered that it was improper for him to love a woman from the low tribe of the hunters. At that moment they heard the sound of approaching drumming and music. Valli warned Murugan that the hunters are wild and angry men, and the god transformed into an old Saiva devotee. Nampi and his hunter's took his blessings and returned home. The old man asked Valli for food, and she gave him some millet flour mixed with honey. Then she took him to a small forest pond, where she quenched his thirst from the palms of her hands. Then he told her, "Now that you have satisfied my hunger and my thirst, do satisfy my love for you." Valli reproached him, and wanted to return to her field. At that moment, Murugan invoked the help of his brother Vināyaka who appeared behind Valli in the shape of a frightening elephant. The terror-stricken girl rushed into the arms of the Saiva ascetic for protection; he dragged her into a thicket and while embracing her revealed his real form, with six heads, twelve arms, and seated on his peacock.

Carried away by this vision of her favourite god, Valli worshipped him and he told her that she was, in fact, the daughter of Tirumal. Valli complied with his wish, and they loved each other. A female companion of Valli questioned the girl about her absence and the striking change in her appearance, but Valli answered evasively. Soon after that, Murugan, again in the shape of a hunter, appeared in front of the two girls, and the companion observed that Valli and the hunter exchanged amorous looks. Therefore, she demanded that the hunter remove himself. He then admitted his love for Valli and he warned the companion that, if she would not help them to meet and enjoy their love, he would resort to the old custom of matal or riding the toy-horse in the village itself. The companion agreed to Murugan's request. As the harvesting time approached, the tribesmen called Valli back to the hamlet and the lovemaking was over. With a heavy heart she returned to the house of Nampi. Her clandestine love affair (kalavu) with the god ended. Her mother noticed Valli's unhappiness and invited soothsaying women who stated that Valli was possessed by the cūr of the slopes and that a ceremony in honour of god Murugan should be organized. Murugan went to the millet field and, not finding Valli there, he came, at midnight, to the hamlet, and with the aid of her companion, Valli and her divine lover eloped. Next morning Nambi's wife discovered Valli's disappearance. The furious hunter-chief organized a party of hillmen in pursuit of the fugitives. When they reached them, they discharged their arrows at Murugan, but the divine cock of the god crowed and the hunters fell dead. Valli lamented their death, but Murugan took her along. On their way they met Narada who explained to Murugan that he should have obtained the consent of the parents. The god therefore returned and ordered Valli to resuscitate the hunters which she gladly did. Murugan then assumed his true divine shape. Amazed and awed, the hunters worshipped him and begged him to return to the hamlet to be married in accordance with the custom of the tribe. The whole village rejoiced. The young pair was seated on a tiger-skin. Nampi placed the hand of Valli into the hand of Murugan and declared them married while Nārada assisted. At that moment, the gods appeared in the air and blessed everyone. Nampi then offered a feast - plenty of honey, millet flour and jungle fruits. After a short stay at Ceruttani (Tiruttani), Murugan and Valli returned to Skandagiri where they were welcomed by Devasena. What is so very thrilling in this story is the fact that almost step by step its structural slots and their fillers are derived from elements of the oldest Tamil tradition. It is the classical Sangam age all over: the heroine born among the hillmen; at the age of twelve, sent to guard the millet field sitting in the paran; the appearance of the god -- i.e. the talaivan, the hero, and his attempts at immediate, clandestine love-making (kalavu); the role of the toli -- the companion of the heroine; the motif of riding the matal-horse; the kaamanoy -- love sickness of Valli due to separation; the soothesaying women, and the veri dance of the velan, arranged to appease Murugan and dispell cūr; the motif of elopment of lovers. It is quite obvious that this story is purely and totally Tamil. I share fully the view that religious phenomena can be best understood on their own plane of reference, that they deserve to be interpreted in religious terms, and that the most fruitful approach to the study of a deity and its myths should be phenomenological and structural: an attempt to apprehend a vision of reality that persists throughout the history of a deity. However, any religious phenomenon is also a psychological, social, and historical phenomenon. A historical-evolutionary study, even a historical-evolutionary interpretation of a deity and its myths is necessary, too, at least at some preliminary stage of its investigation. ValliFirst then, the name of Valli. The Tamil etymology is a simple and straightforward Dravidian derivation. According to an ancient and persistent tradition, the name of the person is derived from the name of the plant, valli DED 4351, found in Ta. Ma. Ka. Kod. Tu. and Te. and a number of tribal languages. The creeper belongs to the Dioscoreaceae. It has a 'winged' stem, and both wild and cultivated varieties; the cultivated varieties have edible bulbous roots. It is mentioned in the glossary of the 99 plants typical for the kurinci region found in Kurincippattu ascribed to Kapilar (ca. 140-200 AD). In the earliest Tamil texts, the term valli in its meaning of this creeping plant occurs at least 18 times. The Skt. valli, also valli 'creeper, creeping plant' is almost without doubt derived from Dravidian, since the Sanskrit term oc curs relatively late, has no plausible Aryan etymology, and refers to a plant typical for tropical India. In Dravidian, the item is found in relatively 'distant' languages like Tamil and Telugu, and in early records, referring to a plant used almost prehistorical tropical forest cultivation. According to the myth, Valli the person was so called because she was found in a pit dug out while gathering the edible tubers of the valli-plant. Valli as a plant is mentioned in Akam 52.1 and 286.2, Puram 316.9, Nar. 269.7 and Parip. 21.10. The roots (kilanku) of valli are mentioned explicitly in Puc. 109.6 and Kal. 39.12. In Ainkur. 250 a vague but probably significant connection is mentioned between the worship of Murugan and the valli plant. The earliest references to Valli the person, the beloved and consort of Murugan, are relatively few, though increasingly important. In their probable time sequence they are found in Nar. 82.4, Tirumuruk. 102, Parip. 8.69, 9.8, 9.67, 14.22 and Cilap. 24.3. Thus we have all in all only seven relatively early (i.e. pre-bhakti, pre-sixth Cent. AD pre-Pallava) references to Valli as the god's beloved and/or spouse. One of the references belongs to the earliest strata of Tamil texts: Narrinai 82.4. The poem belongs to the kurinci sub-type of akam poetry and may be dated to the 2nd-3rd Cent. AD. It says: niye/ennul varutiyo nalnataik koticci murukupunarntu iyanra valli pola "Oh you, girl of the mountain tribe whose gait is beautiful, will you come to me like Valli who had gladly agreed to join Muruku?" The erotic association is clear: the hero invites the girl to join him as Tamil term punar in murukupuaarntu valli means to reunite, particularly sexually, to cohabit'. It is therefore clear that in the 2nd or 3rd Cent. AD the story of Valli and Murugan -- i.e. the nucleus of the myth narrated above in the sense of Valli being the beloved and sexual partner of Murugan -- was sufficiently well-known to provide a divine model for human behaviour and a material for the poet to draw a simile from. It is worthwhile noticing that at the time when this story was obviously well-known in Tamil India, and hence must have been known there even before the 2nd. Cent., nothing at all is heard yet of a Valli in any Sanskrit or North Indian source. TirumurukarruppataiThe Tirumurukarruppatai is a text qualitatively different from almost all other so-called Sangam poetic texts, not in that it would be much later in time but that it is different in character and purpose. Unlike the other bardic poems, it is a religious text par excellence, a text devoted (for the first time in the development of Tamil textual tradition) exclusively to the worship of a deity -- Murugan. From the point of view of its attitude towards the process broadly termed Sanskritization, Tirumurukarruppatai is certainly integrative and syncretistic. The god's consort Valli is mentioned once as the 'innocent daughter of the mountain-tribe with creeper-like waist, at whom one of the six faces of Murugan smiles in serenity'. Tirumurukarruppatai is also probably the earliest Tamil text which, in agreement with its syncretistic-integrative tendency, mentions for the first time, the northern, imported, consort of Skanda-Murugan -- if not by name than at least by allusion. The term karpu in line 6 of the poem (Skt. kalpaa?) by which Devasena is alluded to means 'fundamental duty, rule, chastity'. It refers to a form of marriage which is according to the rules of the Brahminic order; and indeed Devasena alias Tevayanai has become the symbol of the regular Hindu marriage performed according to Brahminic Hindu rites while Valli, as is clear mainly from the Paripatal, obviously was considered the symbol of kalavu, love-relationship based on katal 'love affection' and of marriage performed according to pre-Aryan, non-Brahminic rites. In fact -- and this is the important conclusion of this talk -- Murugan and Valli are mythic exemplars of the ancient and indigenous Tamil motif of kalavu -- the pre-marital union of lovers. |