|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mailam: A Murukan temple at the crossroads of myth and local cultureமைலம் முருகன் ஆலயம் புராணக் கதை: அதன் வளர்ச்சிby François L' Hernault

The more recent temples are, the greater the chances of discovering a few historical elements and thus of knowing the conditions of their foundation. This is the case with the Mailam temple, which is not earlier than the beginning of the eighteenth century. The study of this temple enables one to observe interactions between well-known and established mythical traditions and local realities, as well as showing how these two aspects intervene both in the story and in the iconography. Mailam is located fifteen kilometres from Tindivanam and thirty from Pondicherry. The temple, situated on a small hill (fig.1), is connected with a village on the Coromandel coast, Bomayapalaiyam, very near Pondicherry, where a Vera Saiva mutt is found (fig.2). According to the name, bomma or bomme, derived from brāhmana.1 This was a village donated to Brahmans, as is confirmed by the sthala purāna in which Bomayapalaiyam is also named Brahmapuram. The street leading to the mutt is still called agrahāra. It is known from the private diary of Ananda Ranga Pillai, the dubash under Dupleix, that Dupleix visited, in 1744, the head of the mutt and offered him a few yards of cloth and bottles of rose water.2 In another passage, dating from 1746, Ananda Ranga Pillai mentions that the swāmi of the mutt cities three pontiffs during this twenty-four year period. Be that as it may, of interest is what Ananda Ranga Pillai has to say regarding the succession to the swāmi. First, he states that a certain Turaiyar Pachai Kandappaiyur, who was leading an ascetic life in Palani, was installed as head of the mutt.4 However, four days later, he corrects himself to say that Turaiyur Pachai Kandappaiyur, who had come to install the new pontiff of the mutt, desired to visit Pondicherry before returning to Turaiyur.5 This shows that Palani had control over the mutt. All the heads of the Bomayapalaiyam mutt are named Śivañāna Bāla Siddha, which calls clearly to mind that Palani is a hill inhabited by siddha-s and devoted to Murukan, or more specifically, to Murukan in his form of ascetic and young (bāla) god. These two aspects are generally concomitant, probably on the basis of their connotation of innocence and purity. The storiesAccording to the sthala purāņa of Mailam, it was the duty of Şaŋkugaņa, a gaņa in Śiva's following, to stand guard at the grove where Pārvatī was bathing. He failed in this task as he did not prevent Śiva from entering and, because of this, he was cursed by Śiva, who announced that he would have to fight with Murukan and teach the vedasaivāgama-s for many years.

Having been thus cursed, the gaņa, in the form of a young child named Bālasiddha, descended to earth, to the village of Bomayapalaiyam. Knowing that he could be liberated only by Murukan, and following the advice of Nārada, he went to Mailam, the hill whose name is linked to the peacock of the god (mayil), for it was there that the asura Sūrapadma assumed the form of a peacock so as to obtain liberation from Murukan. Despite the intervention of his consorts, Vaḷḷi and Devasenā, Murukan refused to do away with the malediction weighing upon Saŋkugaņa because it had come from Śiva. By way of reprisal, Murukan's consorts slipped away from him and became siddha kanni-s (abstinent ascetics), taking refuge in their palace. disguised as a hunter, Murukan attempted to enter the palace and confronted Saŋkugaņa. The guardian very soon recognized the god, who immediately rid him of the curse and asked him to remain on Mailam hill. Murukan married Vaḷḷi and Devasenā, and Saŋkugaņa, for his part, asked Murukan to always remain present at Mailam with his wives in the form of bridegroom (kalyāņa kolam). This theme of the separation of consorts is a motif at once aesthetic and religious, which is sometimes expressed in a quite pronounced erotic mode. In Mailam, it appears in the ten-day brahmotsava in the month of Paŋkuni. The fourth day is devoted to the amorous quarrel, tiruvūt@al, in the course of which Vaḷḷi refuses to meet Murukan. Contrary to the Śiva temples where Sundarar is customarily the mediator, in Mailam, it is Brahmā. According to this account of the sthala purāņa, it appears that Saŋkugaņa is an asura created for the occasion, an asura with neither personality nor consistency, as is clearly shown by his name, saŋkha or saŋku, conch. He may simply be one among the numerous gaņa-s blowing conches, as is very common on the wooden chariots. Moreover, his story is borrowed from another one, that of Gaņapati, guardian of Pārvatī's privacy. In fact, this is the classical from of any, asura to whom the god, in his avatara form, accords liberation subsequent to violent combat. Most important is that Saŋkugaņa is explicitly said to be Bālasiddha. This is the main link which, not withstanding a mythical presentation, shows that the temple was created by a head of the mutt. The conclusion of the sthala purāņa is clear in this matter: Bālasiddha also asks Murukan to remain as Kalyāņa Kolam in Mailam and in Bomayapalaiyam, in the mutt created by him.

The iconographySeveral features in the iconography of the Mailam temple testify to this duality. The temple possesses two processional chariots that are used for the brahmotsava in Paŋkuni. They are decorated with sculpted panels representing diverse forms of Śiva: Bhikśāt@ana, Gajasam@hāramūrti, Kalāntaka, etc., and Sarasvatī Kāma, Kriśņa, among other deities of the pantheon. The other panels, linked with local history, are of two types. There are, first, panels connected with both Murukan and the mutt and, second, panels relating solely to the mutt. Two panels represent episodes of Saŋkugaņa fighting against Śiva, and then against Murukan. In the first scene involving Śiva, the representation deviates singularly from the story. Śiva, bearded and wearing a turban, is in the process of copulating with his consort, while Saŋkugaņa, the guardian's club in his hand, reaches up to "save" the latter and pulls her by her hair (fig 3). The second scene is more allusive and the wives of Murukan do not appear: only Murukan seizes the guardian who joins issue, his arm raised as a sign of combat. It is certainly because Saŋkugaņa is reincarnated as a young child that the birth of Murukan is represented. This is a rare scene, with the exception of Darasuram where amidst reeds, his place of birth, the baby god is taken by Śiva, who returns him to Pārvatī. In the next scene, she is giving him her breast (fig. 4).

In Mailam, the krittikā-s hold six small Murukan's in their arms, seated on lotuses. On an adjacent panel, at Śiva's side, Pārvatī gathers a long and Nandikesvara as lotus bearing a six-headed Murukan (fig5). On a third panel, between Pārvatī and Nandikesvara as worshippers, Śiva is standing, bearded and armed with his trident, the kettle-drum and fire, and holds the child Murukan on his arm (fig.6).

Another type of representation, also quite rare, is Murukan teaching, a form of the god related to his activities as well as those of the head of a mutt. One scene is on Gaņapati's chariot and another on that of Murukan. In one case, Murukan is seated on a pedestal with a book in his hand, giving a lesson to Śiva, who is standing with joined hands (fig.7). In the other, Subrahmaņya, again on a pedestal, is making the gesture of teaching in front of Śiva, who stands in respectful attitude of listening, one hand before his mouth (fig.8) A third representation is the illustration of a passage from the Tamil Skanda Purāna recounting the incarceration of Brahmā as a consequence of his inability to recite the Vedas. The prison is a frame spiked with thorns in which Brahmā is held, kept watch over by a mustached guard, dagger in hand. Next to this, a walking Subrahmaņya is in the process of imprisoning Brahmā (fig.9).

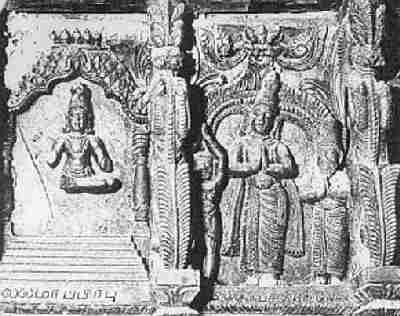

Five panels bear vīra saiva figures. On the first panel, the identity of one of them, who is wearing a tiara and seated on a throne beneath a canopy, is engraved in Tamil on a step of throne: Alamma Prabhu (fig.10). The latter was a spiritual master from the twelfth century known for his ascetic rigour and was contemporaneous with Basava. On the adjacent panel, three men standing with joined hands are certainly worshippers of Alamma Prabhu. The inscription, Prakās'a Praveśa Vēlaya, must be the name of the central personage, who is larger than the two others (fig.10). On the third panel, a sage is seated on a throne beneath a canopy (fig.11). he has a beard and moustache and long hair scattered on his shoulders and wears around his neck a necklace of rudrākśa and a linga. One hand is in abhaya-mūdra and the other holds the linga of the vīra saiva-s. Beneath is an inscription: "Bāla siddha Saŋkugaņar", confirming the assimilation of the two personages. Its date is 4245 of the Kali era, that is, 143 AD: this is obviously a mythical date suitable for a founder.

On the fourth panel, a siddha, flanked by two worshippers, is seated with crossed legs on a throne in the form of recumbent lion (fig.12). He has the chignon of an ascetic, a moustache and beard and wears a linga around his neck. The inscription gives his name: Pāvala Cuvāmi, and the date is 3245 of the Kali era, or 1143 AD, which is more or less the period of Basava and of Alamma Prabhu. As the dates, ten centuries in the past, are similar, it is possible that the second, historical, date had determined the choice of the first. On the last panel, a figure is standing, dressed in a dhoti, shoulders covered by a large scarf. He has rudrākśa-s and a liŋga around his neck and is wearing the sandals of an ascetic (fig.13). He is holding the staff of the pontiffs and near to him are offerings placed on a low table. The inscription indicates that it is matter of the installation (makut@a abhiseka) of the eighteenth Bālaya Swāmi. The date in Arabic numerals is 25.2.28, quite obviously 1928, as it is known from the documents of the mutt that he died in 1965 and that he was succeeded by the present pontiff, the nineteenth, who was installed in 1965. The Mailam temple, as doubtlessly most temples, is anchored in a very particular cultural idiom that comprises its originality. Endnotes

Francoise L'Hernault is a research fellow with the Ecole Française d'Extrēme-Orient in Pondicherry (French Institute for Oriental Studies) who has specialized in the architecture and the iconography of South India. She has undertaken studies on the Darasuram, Gangaikondacholapuram and Tiruvannamalai temples and on the iconography of Subrahmanya in Tamilnadu. This paper was presented at the First International Conference Seminar on Skanda-Murukan, December 1998Index of research articles on Skanda-MurukanOther articles about Kaumara Iconography and Art History:Karttikeya in ancient Cambodia

Karttikeya in ancient China Skanda in Chinese Buddhism Index of research articles on Skanda-Murukan |