|

|

|

| |

Murugan versus SkandaThe Aryan appropriation of a tribal Dravidian godUrmi Chanda-Vaz

|

AbstractThe age-old Aryan-Dravidian debate shows up repeatedly in the Indian cultural landscape. The Dravida people claim primacy on indigenous grounds, while the Aryans wield their Brahmanical supremacy. The Vindhyas have kept a resolute distance between the northern and southern cultures, despite centuries of attempted Aryanisation. Among the many cultural symbols appropriated by Indo-Aryans, the folk god Murugan is a fine example. Several modern scholars have studied the Puranas as a tool for acculturation and rightly so. The ancient god of the hills, who had an independent cult, was slowly inducted into the Shaiva fold through various Puranas. More mainstream sanction was begotten with Adi Shankara's Smarta tradition. The popular warrior god, who had little mention in the Vedas, suddenly makes a glorious appearance in the post-Vedic period. Who was Skanda? Where did he come from and why? How similar or dissimilar are Murugan of the South and Skanda-Kartikeya of the North? This paper traces the origin and development of this god in Aryan India, whilst comparing him with its southern counterpart. By studying the iconographic and mythological motifs, this paper hopes to understand the religious and political motivations behind this appropriation. Were the Aryans wholly successful in the acculturation of Murugan? The tussle started in the early centuries of the Common Era and continues to this day. |

Introduction

The festival of Thaipusam celebrated in the Tamil month of Thai (around January-February) is extraordinary to say the least. Thousands of faithful across Tamil Nadu, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore and even South Africa participate in this annual festival that celebrates the giving of the divine weapon Vel to Murugan by the goddess Durgā. Armed with this vel, Murugan conquers evil and ignorance. As the moon shines in its full splendour, droves of Murugan devotees walk in a procession carrying a kavāḍī or a 'burden'. In its simplest form, a kavāḍī could be a pot of milk, but more extreme forms include fixing them to one's body with sharp metal hooks. The kavāḍī is a symbol of the burden of one's past sins and carrying it as an act of atonement.1 The sight of devotees walking along with many thin spears and hooks piercing their mouths and bodies is an amazing one. These devotees seem to be in a trance-like state and are seemingly unhurt. What other than faith and extreme mental control could make such a spectacle possible? It is hard to say. But what can be said with absolute certainty is that the people of South India, especially Tamils, zealously worship Murugan.

Tamil Kaḍavul or the God of the Tamils

The term 'Tamil' has vast cultural connotations. In addition to the language and the people, the term 'Tamilāgam' was used to refer to all of of ancient peninsular India2. Most of South India's ancient history comes from Sangam literature, which is recorded in Tamil. It, therefore, comes to pass that most cultural emblems of South India have a Tamil legacy, including their gods. Incidentally, one of Murugan's many names is 'Tamil Kaḍavul', meaning 'God of the Tamils'. In this section, we look at one of the earliest Tamil gods from whom the cult of Murugan evolved. In pre-Aryan South India, the land was classified into five types, according to its primary geographical feature or tinais. These were Mullai (forest land), Marutham (agricultural land), Neithal (coastal land), Pālai (dry, arid land), and Kurinji (hilly land)3. Each was associated with a god who was its guardian.

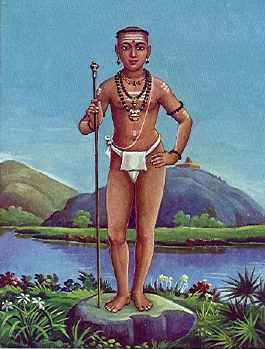

The earliest religious practices of southern India find references in Ṭolkappiyam, an ancient Tamil text on grammar, belonging to the Sangam Age.4 According to this encyclopaedic work, the presiding deities were: Mayon in Mullai, Ventan or Intiran in Marutam, Varuṇa in Neithal, a Kali-like malevolent goddess in Pālai and Śeyon in Kurinchi.5 Of these, Śeyon 'the red-complexioned god' seems to have been the prototype for Murugan. K.R. Ventakaramana6 lists some of his characteristics. “The oldest Tamil hymns refer to him as the deity of the hilly regions, and the god of the tribes of hunters – Velan (he who carries a vel or spear). He was believed to induce violent passions of love in the minds of girls, and was propitiated by magic rites. His priests and priestesses, wearing clusters of vengai flowers dripping with honey, sang and danced...” In early Sangam literature, he is also associated to local flora and fauna, particularly, the elephant, peacock, and the rooster.7 One of Murugan's names is 'Guha', which means a 'hidden' or 'cave' and it is probably a reference to the earlier form of the god, who roamed the caves and hills. He is also said to be related to the inauspicious and dangerous Grahas and Mātras by some scholars.8

These clues are strongly evident of a folk deity – something of a hunter-lover-chieftain – of the indigenous mountain tribes like Veddas and Kuravas9 in the early centuries BCE. Thus, Murugan worship in his erstwhile form of Śeyon goes back centuries in the Tamil country, traceable at least to the Sangam Age. In fact, some scholars10 even argue that Skanda worship may have been known even to the people of the Indus Valley civilization! The basis for the argument is a Harappan seal featuring six female figures and one male figure, who are thought to be the six Krittikās / Matrikās accompanied by Skanda. While this is not a popular theory, it goes on to assert that Skanda is indeed seen as one of the most ancient Indian gods.

Śeyon to Skanda: Literary references

Aryan influence began to manifest in Tamilagam around the 4th century BCE 11, with the advent of sage Agastya, a semi-historic personage. After this point, the local folk gods like Skanda were swiftly and systematically inducted into the Brahmanic fold. However, many Brahmanas from the Agastya cult believe that it was they who brought Skanda with them to the south when they migrated after their guru.12

The earliest possible references to Skanda occur in the Rig Veda by the name Kumāra13, who is identified with Agni. He is, therefore, also known as 'Agnibhuh'. He is also identified with Rudra in some Vedic stories.14 Skanda came to be recognised as the lord of petty criminals just like his 'father', Rudra. The Mricchakaṭikā (Act 3) of Sudraka refers to thieves and burglars as 'Skandaputras'. Such attributes retained the flavour of the ancient tribal god of the hills and the pillaging ways of gypsy tribes. However, these references in the Vedas were few and far between. Once Buddhism began to spread aggressively from 6th century BCE, the Vedic religion moved quickly from the exclusive fire sacrifice culture to embracing local gods and cults in a bid to remain popular.

Skanda seems to have been not one but a class of similar gods in the earliest period. In addition to Śeyon, we encounter him in different forms and names in different scriptures, epigraphs and coins. But consequently we see an amalgamation and the creation of one entity known in North India Skanda-Kārttikeya. In one of the oldest Upanishads – the Chānḍogya Upaniṣad (composed around 8th cent. BCE 15), we meet him as Sanat Kumar.16 Though Sanat Kumara is one of the four Kumara sages, this identity is based on the attribute of everlasting youth that is also possessed by Skanda. Much later, around the 14th century CE 17, we meet him as Khanḍobā in Maharashtra, though that is not a very popular notion. Khanḍobā is mostly believed to be an incarnation of Shiva, but given his warrior-like nature, some scholars identify him as Skanda or Subrahmanya.

By the time of the Upaniṣads and Purāṇas, the ruddy-skinned god, Śeyon was drawn specifically into the Shaivite fold, much like his counterpart, Gaṇesa. Nath18 says, “The cults of Gaṇeśa and Kārtikeya as found in the Purāṇas are most outstanding examples of transformation of tribal deities into major Puranic gods.” She adds how the Viṥnudharmottara Purāṇa and Matsya Purāṇa give references to numerous folk gods and goddesses in a bid to incorporate fringe deities into the mainstream.

Acculturation through mythology

One powerful tool of acculturation is mythology. The myth of his birth as Śiva's son is an important one as it inducts him into the mighty Shaiva cult. Skanda's early association with the Vedic Rudra on one hand, and Rudra's evolution into the Puranic Shiva, explains this association. Religious syncretism of the Puranic times was often at play in the creation of such interrelationships between different gods. Nath asserts, “In the case of Śiva-centric current, we find that it was largely through the extension of Śiva's immediate family circle that deities with a prominent tribal and regional cast and background such as Ganeśa, Skanda, Pārvati or Durga could be integrated into the Puranic fold.”19 Śiva was perhaps the perfect choice for assimilating other cults because of his borderline personality: neither tribal, nor mainstream; neither fully ascetic nor completely householder.

The most popular stories of Skanda's birth occur in the epics. The epic period seems to have been the time when this god rose into prominence. With slight variations, one sees the following birth story being recounted in several sources. Some of the sources include the Rāmayaņa, the Kumārasambhava, the Vāyupurāṇa , and the Skandapurāṇa. More references occur in the Bhāgavad Gitā, Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra and Patanjali's Māhābhāṣya.20 The most elaborate story of his origin occurs in the Skanda Upākhyān of the Araṇya Parva of the Māhābhārata. In his doctoral thesis title 'The Early Cult of Skanda in North India: From Demon to Divine Son', Richard D Mann (2003) points out how Skanda is depicted as a malevolent deity in the beginning of the epic and becomes an auspicious one by its end.

In short, the story tells us how Śiva cast his seed inadvertently into Agni. Even Agni found the power of Śiva's tapas to much to bear and carried it off to the river Gangā (Skanda is also called Gangeya). The Ganga then deposited the fiery sparks in a reed forest (Saravana). Here the baby Skanda (in some versions, six babies) was born with six heads (Śanmukha) and twelve arms and was nursed by the six Krittikās (Pleiades). This myth cleverly unites multiple confusing origin stories. It justifies all tales about Skanda being son of Rudra/Śiva, Agni, Gangā, and the Krittikās (the name Kārtikeya comes from Krittikās). No other god in Hindu mythology has so many contenders for parentage. It can be seen as an indication of his popularity and that the Vedic fold desperately tried to woo his followers to bolster their numbers.

Further, in the story, we learn of Indra's initial rivalry with and later acquiescence of Skanda. In the period of rivalry, Indra once strikes the child god with his vajra but manages to slice off only a part of his leg. From this springs forth Viṣākha bearing a spear. In some places, Viṣākha is said to be Skanda's brother, and in others, he is thought to be Skanda himself. From Skanda also emanate hordes of Kumāras and Kumarïs, who like Rudra's ganas, are fierce fighters. Like Indra, Skanda is also associated with military prowess and eventually named the general of the gods. He fights evil demons like Tārakasura, Bāṇāsura and Pralambāsura and the darkness of ignorance.21

Other important myths include the marriage of Skanda to Indra's daughter Devasenā and Valli, a hunter-maiden from the the hills. The names are often thought to have arisen from corruptions/misinterpretations/ associations of the terms 'Deva sena-pati' (the commander of the devas)22 and Vel, Skanda's ever-present spear. Therefore, they are more the attributes of Skanda than his wives. However, in South India, Murugan in consistently represented and worshipped along with his two consorts. This is one big point of difference between Murugan and Skanda, for the latter is depicted as a staunch celibate ascetic23 in the northern part of India, especially Bengal and Orissa. In fact, celibacy is such an important aspect of Skanda's persona that women are not allowed to enter the few extant Kartikeya temples in North India.

Another popular myth24 explains Murugan's prominent presence in South India. The tale is one of sibling rivalry. Skanda and Gaṇeśa are once fighting over a mango. Wanting to settle their fight, Pārvati asks them to race around the world and says the winner would get the prize mango. Skanda jets off to go around the earth, while Gaṇeśa circumambulates Śiva & Pārvati, claiming they are his world. An obviously quicker Gaṇapati is declared the winner, much to Skanda's chagrin. Alleging favoritism, Skanda sulkily goes off to the south of India and settles there. Many other myths about Skanda's heroics seal his image as an Aryan sophisticate, having been associated with the likes of Śiva, Agni and Devi. Here, his evolution from a plundering tribal god into a protective deity is complete.

Historical and archaeological evidences

The mythological rise of Skanda mirrors his historical rise and vice versa. The earliest archaeological evidences of Skanda can be placed in the first centuries of the Common Era, which was also when the epics and Puranas were being written and consumed in full force. It is through several statuary, epigraphical and numismatic evidences that we know about the existence of several Skandas as purported earlier.

Kushana coins from the 1st century CE, belonging to King Huvishka feature a number of Indo-Bactrian deities. Of these, the Skanda-type coins are well known. According to eminent numismatist, Parmeshwarilal Gupta, “Besides Śiva and Umā, his son Kārtikeya also finds a place on the gold coins. He is shown there alone with the name Maasena (Māhāsena); in a pair with the label Skandakumaro Vizago (Skandakumara and Vishakha). Skandakumāra, Māhāsena and Viṣākha are three different names of the same god Kārtikeya, but these coins suggest that each had their separate identity.”25 There are also Kushana coins featuring the goat-headed deity, Naigameṣa – another god associated and identified with Skanda. One of Skanda's six heads is that of a goat (his Agni legacy), much like Naigameṣa's head and both were prayed to for the protection of children.26 The cultic significance of Skanda-Naigameṣa can be inferred from the number of crude terracotta goat-headed anthropomorphic statues that have been discovered in the Mathura region.27 These coins depict Skanda in a kingly manner, complete with a lance-like weapon and a cape. The epic template of the god as a warrior seems to have influenced the iconography on these coins. Nilakanti Shastri (as cited in Clothey, 2005) also mentions 'certain Ujjain coins of the third or second century BC' that feature the legends 'Brāhmaṇya' and 'Kumāra'. The Satavahana kings from Deccan also seemed to be patronising the Shiva-Skanda cult simultaneously in the early centuries of the Common Era, given that their kings had names like Siva Skanda Satakarni28 (145-152 CE).

Similar coins belonging to the Yaudheyas – dated roughly between the 2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE – offer further evidence of the antiquity of Skanda worship. This warrior clan hailed Skanda as their tutelary deity and worshipped him in the form of Brāhmaṇyadeva-Kumāra, in close association with the goddess Śaṣṭhī.29 A number of bas relief panels from Mathura belonging to the same period also depict Skanda along with the Matrikās/Kritikās.30 This implies that while Skanda's martial aspect was beginning to gain popularity, his older association with inauspicious mother goddesses was not forgotten.

A number of their silver and copper Yaudheya coins feature a six-headed deity, while some show a one-headed god who holds a spear in one of his two arms and has a peacock by his side. Skanda's identity is further strengthened through the inscriptions31 on the coins. Two of them can be translated as follows:

“Of Brāhmaṇuja Skanda, the divine lord of the Yaudheyas”

and

“Of Kumāra, the divine lord Brāhmaṇyadeva.”

While the iconographic representation and nomenclature makes it clear enough that the deity in question is Skanda, the choice of epithet 'Brāhmaṇyadeva.' is unique. Nowhere in the scriptures, before or during the time of the Yaudheyas, has this name been used for Skanda. While there is no conclusive evidence on what the name means, it can be conjectured to be a Brahmin connection.

The Brahmanical form of Skanda worship seems to have gained ground in South India around the same time. The Ikshvaku dynasty based in modern Andhra Pradesh was founded by King Shantamula I in the 3rd century CE. He was a staunch follower of both – the Brahmanical religion and the god, Skanda. He has been described in the Purāṇas as being “favoured by Māhāsena”.32 The names of kings and relations in the Ikshvaku genealogy, like Khandasiri, Kharhdasa-garamnaka, Khandavi Sakhamnaka where Khanda stands for Skanda33 further testify their fondness for the god.

The Guptas were next in carrying forth the glory of Skanda-Kartikeya in Northern India. From 4th to 6th centuries CE of what is termed as India's Golden Age, the warrior god enjoyed much patronage.34 Many Gupta coins, especially those commissioned by Skanda Gupta and Kumara Gupta depict the god, especially through the peacock motif. The names of the kings also bear testimony to the popularity of the deity. It is to be noted that by this time, the several forms of the god, like Viṣākha and Māhāsena, had coalesced and had become the singular Skanda-Kārtikeya we are familiar with.

Political and religious motivations

The deification and evolution of Skanda as a royal martial god has been connected by scholars like Mann and Clothey primarily to the idea of kingship. From the Magadhan period, the ideas of state and kingship became manifest. The Kushanas, with plenty of Greek influences, solidified the model. The Indian society which once acknowledged many chieftains now fell in the ambit of a few kings. It was during the span of 200 BCE to 500 CE that the epic and Puranic conception of Skanda materialised, and he became a kingly warrior god worthy of the adulation of kings. Skanda, who was the brave 'Vedic' commander of the gods' armies, and Skanda, who was the tribal god shielding children from diseases were fused together to create a perfect deity for kings who protected their subjects in the time of war and cared for them in times of peace. These political motivations were therefore partly responsible for the Aryanisation of one of the original Dravidian gods.

Among religious motives of the changing role of Skanda was the rise of the Shaiva cult. What started as a move to Brahmanise and thus 'legitimise' Skanda in the growing pantheon of the Vedic religion, ultimately turned him into something of an inferior deity. Despite the cult popularity he enjoyed in North India in the early centuries of the Common Era, he could not stand up to the all powerful Śiva and the increasingly popular Gaṇeśa. From an independent tribal warlord, he was relegated to the position of a dutiful and perhaps less favoured son. It was time to find greener pastures.

Skanda goes South

Towards the end of the 5th century CE, the Gupta stronghold over north India started loosening. With the waning power of the kings, their patron deities started waning too. Skanda, especially faced stiff competition from his brother, Gaṇeśa, and moved south as the latter's cult started gaining prominence. Ghurye (as cited by Pillai: 1997) opines that by the end of the 5th century, most of Deccan – including present day Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu – were in the sway of Skanda worship. We noted above how Skanda worship started receiving an impetus from the 3rd century CE onwards, thanks to the Ikshvaku kings.

The Pallavas took it upon themselves next to maintain the legacy of Skanda in the form of Murugan and Subramaṇya from the 4th century CE onwards. A Pallava king from this period clearly stated his allegiance to the Śiva-Skanda cult through his name, Śiva-Skanda-Varman. The earliest archaeological evidence of Skanda from that period comes in the form of a panel at Mahabalipuram, dated to 675 CE 35, where the god is depicted with his 'parents', Śiva and Pārvati.

Legend also has it that a Chera king, Perumal, built the famous Subramanya temple at Palani in Tamil Nadu in the 7th century CE.36 Next, the Pandyan kings also seemed to have forward the Skanda-Subramaṇya cult, as testified by an inscription of of the king Varaguna Maharaja II. The inscription, dated circa 814 CE37 claims that the king was indeed a devotee of this god. The next patrons came in the form of the illustrious Cholas. Although the Cholas were primarily Śiva bhakts, nearly all of their Shiva temples featured Subramaṇya in a sub-shrine.38 Sometimes, Bala Subramaṇya – the child version of Skanda – would also get a temple exclusively to himself like the temple at Kannanur.39 Somaskanda bronzes are an important aspect of the Skanda heritage too. An 11th Century bas relief sculpture40 at Tiru Vengaivasal featuring Subrahmaṇya in veerasana holding a rosary and the vel adds to the list of historical and religious evidence. Conceiving Subramanya as a guru and a healer like the Shiva, which is a stark contrast to his earlier malevolent form, fixes him firmly in the Shaivite religious tradition.

The parallel development of the Smārta tradition during the Puranic Age assured an important position for Skanda in the pan Indian religious map. The Smarta tradition, thought by some to have been formulated by Ṡankarācārya41, is a syncretic school which legitimizes and equalizes the worship of a family of deities. The Pancarātra school comprised Śiva, Devi, Gaṇeśa, Viṣnu and Skanda. A variant, the Ṡanmata school, added Surya to the mix, thereby giving believers a clutch of six principal deities to choose from and worship. Albeit part of a 'family', Skanda enjoyed a fair amount of attention.

In addition, compositions like the Skanda Purana (Kanda Purana in Tamil), Skanda Samhitā and the Skanda Āgamas cemented his place in the Indian religious landscape. Saint-poets like Kachiappa Sivāchāryar (12-14thth century), Arunagiri (15th century CE) and Kumara Guru Para (17th century CE) wrote devotional poetry in praise of Murugan and catapulted him to glorious heights in public imagination, especially of the Tamil people.

Conclusion

The fate of gods and men is inextricably connected. The forces of religion depend on and are defined by socio-political factors. The rise, fall and resurrection of Indian gods can be studied as the best examples of this phenomenon. Skanda's story, as we saw it, is a case in point. His origin in pre-Aryan Tamilagam, the consequent ascent and decline of his Aryanised Skanda-Kartikeya form in North India and his return and popularity to South India is an example of the trajectory of an Indian god's career.

Today, Skanda is extremely popular and is revered by many names such as Sarāvana, Amurugam, Gurugruha, Guhan, Subrahmanya, Vadivelan, Senthil, Swāminātha and Ṡanmukha among others. Over the centuries, the forces of Vedic religion and the ideals of state and kingship led to the appropriation of this once powerful tribal god, and turned him into the kingly Skanda-Kartikeya, son of Shiva. But Murugan eventually found his way back into the Tamil heartland, where he began his journey as Śeyon many centuries ago.

- Abram, D., & Edwards, N. (2003). The Rough Guide to South India (p. 517). Rough Guides.

- Kumar Raj (2003), South India in Essays on Indian Society, (p. 66), Discovery Publishing House

- Pillai, S. (1994). The Contributions of the Tamils to Indian Culture: Socio-cultural aspects (p. 20). Madras, Tamil Nadu: International Institute of Tamil Studies.

- Mehendale, M A. (2001). Language and Literature. In The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Age of Imperial Unity (7th ed., Vol. 2, p. 293). Mumbai, Maharashtra: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Clothey, F. (2005). Murukan in Early South. In The Many Faces of Murukan: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God (Reprint ed., p. 24). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Pvt.

- Ventakaraman K R, (2007), "Skanda Cult in South India" in The Cultural Heritage of India, (p 309), The Ramkrishna Mission Institute of Culture

- Clothey, Op. Cit. (pp 26-32)

- Mann Richard (2011) The Rise of Mahasena: The Transformation of Skanda-Karttikeya in North India from the Kusana to Gupta Empires, p 2, BRILL

- Ventakaraman Op. Cit. (p 311)

- T.G. Aravamuthan and B Y Volchok have argued that the IVC seal in question represent the Kritikas and Skanda

- Kumar Raj, Op. Cit.

- Pillai Devadas S. (1997), Indian Sociology Through Ghurye: A Dictionary, (p 4), Popular Prakashan, Delhi

- Sastry Kapali TV, Pandit Pundalik Madhav (1967), translation of The Rigveda Samhita Vol 1, (p 167), Sri Aurobindo Ashram

- Narayan Aiyangar (1987), Kumara in Essays on Indo-Aryan Mythology Vol 1 (p 29), Asian Educational Service

- Hudson D (2008), The Body of God : An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram, (p 36), OUP

- Narayan, Op. Cit. (p 68)

- Parmeshwaran (2004) The Khandoba Cult in Encyclopaedia of The Shaivism, (p 73), Sarup & Sons

- Nath Vijay (2001), Acculturation Process Mythicised in Puranas and Acculturation: A Historico-Anthropological Perspective, (pp 98-99), Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. Delhi

- Nath, Op cit., pp. 98-99

- Clothey, Op. cit. p 57

- Clothey, Op. Cit. pp 50-55

- Bonnefoy Yves (1993), South Asia, Iran and Buddhism in Asian Mythologies, (pp 92-93), University of Chicago Press

- Chatterjee Asim Kumar, (1970), The Cult of Skanda-Kārttikeya in Ancient India, (p 103), Punthi Pustak

- Smith David, (2008), Hinduism and Modernity, (p 143), John Wiley & Sons

- Gupta, P. (1996), Coins of the Kushanas and their Successors in Coins (4th ed., Vol. Reprint, p. 38), Delhi: National Book Trust.

- The Baudhayana Sutra links Skanda to the cure of children or kumaras

- Mann Richard D (2003), The Early Cult of Skanda in North India (doctoral thesis), (p 208), McMaster University, Ontario, Canada

- Chattopadhyaya Sudhakar (1974), Some Early Dynasties of South India, p 98, Motilal Banarsidass Publications

- Mann, Op. Cit., pp 231-232

- Maity, S., Thakur, U., & Narain, A. (1988). Studies in Orientology: Essays in memory of Prof. A.L. Basham (p. 157). YK Publishers.

- Clothey, Op. Cit., p 59

- Sircar DC (2001) The Deccan after the Satavahanas in The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Age of Imperial Unity (7th ed., Vol. 2, p. 225). Mumbai, Maharashtra: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Agrawala Prithvi Kumar (1967), Skanda-Kārttikeya: A Study in the Origin and Development, (p 50), Benares Hindu University

- Mookerji Radhakumud (2007), The Gupta Empire, (pp 87-88), Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Pillai Devadas S. Op. Cit. (p 302)

- Anantharaman Ambujam, (2006), The Powerful Deity of Palani in Temples of South India, (2nd edition, p 82), East West Publications

- Pillai, Op. Cit..

- Venkataraman KR, Op. Cit. (pp 310-311)

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ghose Rajeshwari (1996), The Tyāgarāja Cult in Tamilnāḍu: A Study in Conflict and Accommodation, (p 98), Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Abram, D., & Edwards, N. (2003), The Rough Guide to South India, Rough Guides

- Agrawala Prithvi Kumar (1967), Skanda-Kārttikeya: A Study in the Origin and Development, Benaras Hindu University

- Anantharaman Ambujam (2006), Temples of South India, East West Publications

- Bonnefoy Yves (1993), South Asia, Iran and Buddhism in Asian Mythologies, University of Chicago Press

- Chatterjee Asim Kumar, (1970), The Cult of Skanda-Kārttikeya in Ancient India, Punthi Pustak

- Chattopadhyay Sudhakar, (1997), Some Early Dynasties of South India, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Clothey, F (2005), The Many Faces of Murukann: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God, Munshi Manoharlal Pvt. Ltd.

- Ghose Rajeshwari (1996), The Tyāgarāja Cult in Tamilnāḍu: A Study in Conflict and Accommodation, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Gupta Parmeshwarilal (1996), Coins (4th ed., Vol. Reprint), National Book Trust.

- Hudson D (2008), The Body of God : An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram, Oxford University Press

- Kumar Raj (2003), South India in Essays on Indian Society, Discovery Publishing House

- Maity, S., Thakur, U., & Narain, A (1988), Studies in Orientology: Essays in memory of Prof. A.L. Basham,Y K Publishers

- Mann Richard (2011) The Rise of Mahasena: The Transformation of Skanda-Karttikeya in North India from the Kusana to Gupta Empires, BRILL

- Mehendale, M A. (2001). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Age of Imperial Unity (7th ed., Vol. 2,), Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan

- Mookerji Radhakumud (2007), The Gupta Empire, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Narayan Aiyangar (1987), Kumara in Essays on Indo-Aryan Mythology Vol 1, Asian Educational Service

- Nath Vijay (2001), Puranas and Acculturation: A Historico-Anthropological Perspective, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. Delhi

- Parmeshwaran (2004), The Khandoba Cult in Encyclopaedia of The Shaivism, Sarup & Sons

- Pillai Devadas S. (1997), Indian Sociology Through Ghurye: A Dictionary, Popular Prakashan

- Pillai, S. (1994). The Contributions of the Tamils to Indian Culture: Socio-cultural aspects, International Institute of Tamil Studies.

- Sastry Kapali TV, Pandit Pundalik Madhav (1967), translation of The Rigveda Samhita Vol 1, Sri Aurobindo Ashram

- Sircar DC (2001), The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Age of Imperial Unity (7th ed., Vol. 2), Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Smith David (2008), Hinduism and Modernity, John Wiley & Sons

- Ventakaraman K R (2007), The Cultural Heritage of India, The Ramkrishna Mission Institute of Culture