|

||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

Faith, Endurance and Penance

|

This man has attached pots of incense to hooks in the skin of his back.

This man has attached pots of incense to hooks in the skin of his back.

|

Steps to the Batu Caves

Steps to the Batu Caves

|

Troupe of percussionists

Troupe of percussionists

|

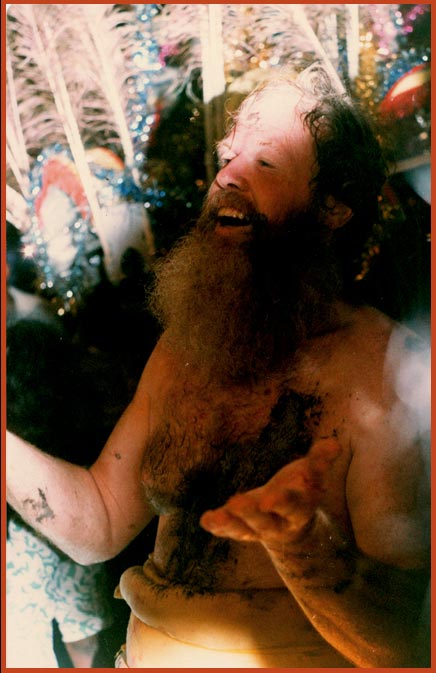

Carl

Carl

|

Hooks stretch this worshipper's skin

Hooks stretch this worshipper's skin

|

Pulling a cart attached by hooks

Pulling a cart attached by hooks

|

Helpful fingers piercing Carl's cheeks as he enters a trance

Helpful fingers piercing Carl's cheeks as he enters a trance

|

Carl carrying his kavadi

Carl carrying his kavadi

|

Image of Lord Murugan framed by the feathers of the peacock, his symbol

Image of Lord Murugan framed by the feathers of the peacock, his symbol

|

Interior of the Batu Caves

Interior of the Batu Caves

|

Thaipusam is a time for Hindus of all castes and cultures to say thank you and show their appreciation to one of their Gods, Lord Murugan, a son of Shiva.

The festival of Thaipusam was brought to Malaysia in the 1800s, when Indian immigrants started to work on the Malaysian rubber estates and the government offices.

It was first celebrated at the Batu Caves in 1888. Since then it's become an important expression of cultural and religious identity to Malaysians of Tamil Indian origin, and it's now the largest and most significant Hindu public display in the country.

Thaipusam is held in the last week of January or the beginning of February, depending on the alignment of the sun, moon and planets, and takes place 13 kilometres outside the Malaysian capital city, Kuala Lumpur in a sacred Hindu shrine called the Batu Caves.

Preparations

Before the festival day itself there's an early morning chariot procession.

Even before the sun rises tens of thousands line the streets to see a silver plated chariot of carved wood containing a statue of Lord Murugan making its way to the Batu Caves where is to stay temporarily.

Devotees approach the chariot with bowls of fruit and even hold babies up to be blessed. Groups of musicians and drummers add to the carnival feel, and pilgrims follow in procession.

This is a colourful event. Women wear jasmine flowers in their hair. Yellow and orange, the colours of Murugan, dominate. Orange is also a colour of renunciation, and is worn by those whose pilgrimage is a temporary path of asceticism.

Deeply reverential

But despite the atmosphere of celebration this is a deeply reverential event for the pilgrims. Carl Vadivella Belle, an Australian follower, says:

...There is something extremely special about Thaipusam, and if I miss it in Australia I feel a sense of loss, of grief that I'm not actually there.

I'm trying to live my life now in accordance with how I feel at Thaipusam, I want that to be my daily experience.

On the day of Thaipusam itself devotees go to different lengths to show their devotion.

Some simply join the crowds processing in the intense heat to the Batu Caves and climb 272 steep steps to say prayers to Lord Murugan at his shrine.

Some carry pots of milk or "paal kudam" on their heads as a show of devotion and love to the god.

Others carry elaborate frameworks on their shoulders called "kavadis", which have long chains hanging down with hooks at the end which are pushed into their backs. (Kavadis can be carried in honour of other deities as well as Murugan.)

Many of these pilgrims are pierced with two skewers (or 'vels' - symbolic spears); one through the tongue, and one through the cheeks.

According to Carl, the piercing by skewers symbolises several things:

- that the pilgrim has temporarily renounced the gift of speech so that he or she may concentrate more fully upon the deity

- that the devotee has passed wholly under the protection of the deity who will not allow him/her to shed blood or suffer pain

- the transience of the physical body in contrast with the enduring power of truth

Still others go even further and pull heavy chariots fastened to metal hooks in the skin of their backs. The skin tugs as they go, and they grunt and growl.

The devotees who go to these extremes say they don't feel any pain because they are in a spiritual and devotional trance which brings them closer to Lord Murugan. The trance can be induced by chanting, drumming and incense.

This is Carl's fourteenth kavadi, and he says:

It does to the uninitiated appear a very violent process, but the fact is that you have a faith - a knowledge - after a period of time that this is not going to cause pain, that the divine will not allow his devotees to suffer on his behalf.

The endurance of what you are doing is enough in itself, and the fact that you are not going to suffer pain is proof of his presence - or one of the proofs of his presence.

Carrying a kavadi

Each kavadi carrier has a group of chanting helpers who support and encourage them throughout the pilgrimage. The helpers protect them from the crowds and form a protective ring around the kavadi so that the wearer can dance freely, reflecting Murugan's role as Lord of the Dance.

Carl says that carrying a kavadi is a very special religious experience:

One of the things that attracted me to Thaipusam was the incredible energy waves... kavadi worshippers seem to radiate this incredible ecstasy that I've never experienced in religious life in any other real context.

And it is something incredibly special that people are prepared to make this commitment to trust a god to take care of their bodies and their welfare in such a quite dramatic way. It's a very dramatic statement to make, if you like, in their belief in the deity.

Another pilgrim describes the experience of the procession like this:

|

|

The first time I had the experience I just felt like I had a strong light coming into me - you feel that somebody is beside you and taking care of you...

Getting close to Lord Murugan

The closeness of the god is something that Carl also feels:

I'm more aware of Murugan as a deity during this trance period at Thaipusam than at any other particular time.

...sceptics have tried to reduce this to some sort of psychosis or something like that, but it's far more than that.

I've tried to study it objectively, but there comes a point where logic has to give way to something which is perhaps deeper and more individual, and this is one of the things about Hinduism: it is what I experience, it is real. I cannot explain it to other people in any greater terms than the ecstasy that I feel.

Hindus believe that each soul has the spark of the divine within, so in actual fact in one way it's a journey outside but it's also a journey inside...so you're in immediate contact with the divine for maybe a short blissful period while you're actually carrying this kavadi.

It's a path towards the ultimate goal of Hinduism which is realisation... While you're in this state of trance you're in a state of divine communion and that imposes this feeling of ecstasy upon you which makes you aware of your ultimate objective.

And of course when you're removed from the trance it also makes you aware of how far you are from your ultimate objective.

At the Batu Caves

Once the devotees have climbed the steep steps to the Batu Caves they have reached the climax of the pilgrimage.

Inside the shrine, the devotees go into a final dance before an image of the deity - that is when the energies are exchanged: "you perceive the god, but you are aware that the god is also perceiving you."

Now the devotees can unhook their kavadis, perform final rituals to the deity and say their prayers.

They hope to return to their usual lives refreshed and invigorated, ready to consolidate and live out the lessons learned through kavadi worship.

Courtesy: BBC World Service

Carl Vadivella Belle, Ph.D. is a former diplomat whose career in the Australian Foreign Service was terminated on account of his devotional activities in Malaysia and Australia.. He is the author of Towards Truth: An Australian Spiritual Journey (Sydney: Pacific Press, 1992) and a practicing journalist and farmer outside Adelaide, Australia. He is also the editor of Bhakti! newsletter published in Canberra, Australia.

He may be contacted at:

48 Adey Road

Blackwood SA 5051 Australia

Tel/fax: 61-8-83700111

E-mail: vadiva@bigpond.com