Reflections on Divinity and Its Traits

Originally published as “Skanda-Murugan: Supreme Deity or Divine Rascal?”

by Patrick Harrigan

For well over two millennia, people of the Indian subcontinent, including Sri Lanka, have adored and worshipped Skanda-Kārttikeya, the ever-youthful wargod who is revered as Kali Yuga Varada, the bestower of grace in the present Age of Quarrel. From Vedic times down to the present day, from holy Mount Kailāsa in the far North to Kataragama in the far South, the cult has managed to adapt and flourish amid the social turbulence of the Kali Yuga. Even today, the cult preserves intact living channels of descending grace or arul accessible to all who seek it.

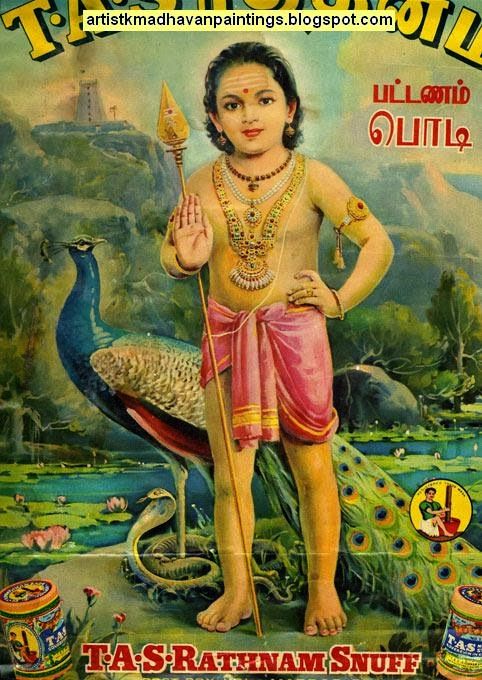

Millions of the faithful in South India and Sri Lanka celebrate Skanda Sasti, the Six-Day ‘War’ Skanda wages against Surapadman, or old Tamil Cūr (literally, ‘terror’ personified). For pious Hindus, it signifies six days of fasting and prayers marked by the lighting of oil lamps. On the sixth day comes the climax, the colorful Cūran Por or titanic war ritually re-enacted in which the child-wargod vanquishes Terror personified with a blow from his Vēl or lance. This most ancient of South Indian gods, Murugan the ‘Tender Youth’, is also the patron god of Tamil language with its pithy utterances of wisdom and sweet songs of fervent devotional tenor.

Living oral and performative traditions continue to preserve the cult’s essentially initiatic character even across linguistic boundaries. Scholarship to date has focused upon textual sources in Sanskrit and Tamil since access to initiatic teachings and practices has always been restricted to dedicated insiders. Nevertheless, devotees of Skanda still stand to gain in depth of appreciation for the ancient deity by becoming aware of some of the findings of modern scholarship.

Methodology

Hence, the analytical tools of modern textual criticism may be employed to assemble a composite picture or character profile as it were of this mysteriously paradoxical solar-lunar divinity. The practitioner (Sanskrit: sādhaka) who engages in contemplation (dhyāna) upon the essential unity of this multi-faceted divinity goes far beyond mere scholarship, plunging deep into the realm of self-annihilation in the absolute Spirit or Godhead. This sublime metaphysical exercise, as daunting as it may appear, nevertheless proceeds from complexity towards ever-greater simplicity and, as such, unfolds with less and less self-effort.

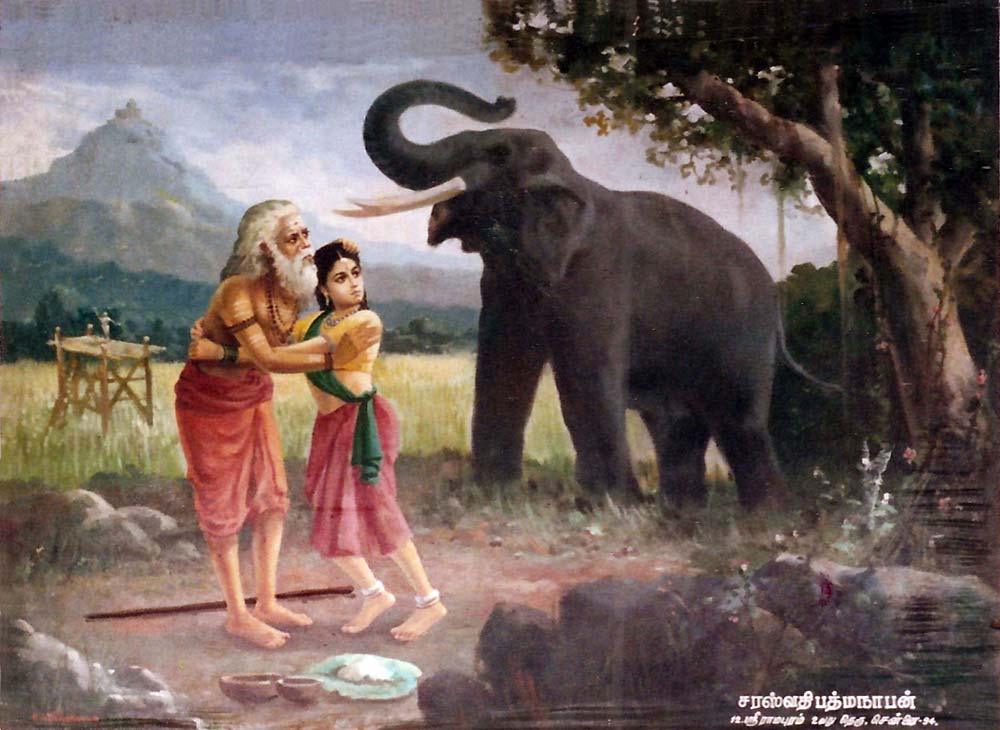

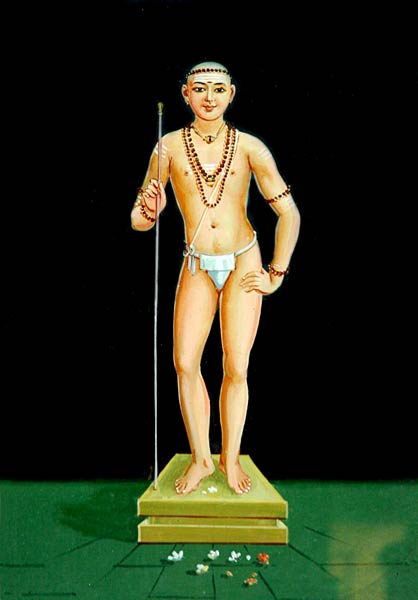

Murugan – The Holy Child

The story of Skanda fairly bursts with familiar motifs distributed worldwide. His most poignant image is that of the Bambino, the Holy Child (and Holy Terror) who is none other than the Sanat Kumāra, eternal youth personified. He is born directly from the unknown and unknowable Source of all life.

However young and tender, he is the Jñana Pandita who expresses the sacred wisdom of cūmma iruttal, the divine art of ‘simply being’, content and happy in the omnipresent busom of his own Mother, from whom he receives his weapon the bright gleaming Vēl (lance) that is his Jñāna-Śakti or Power of Gnosis.

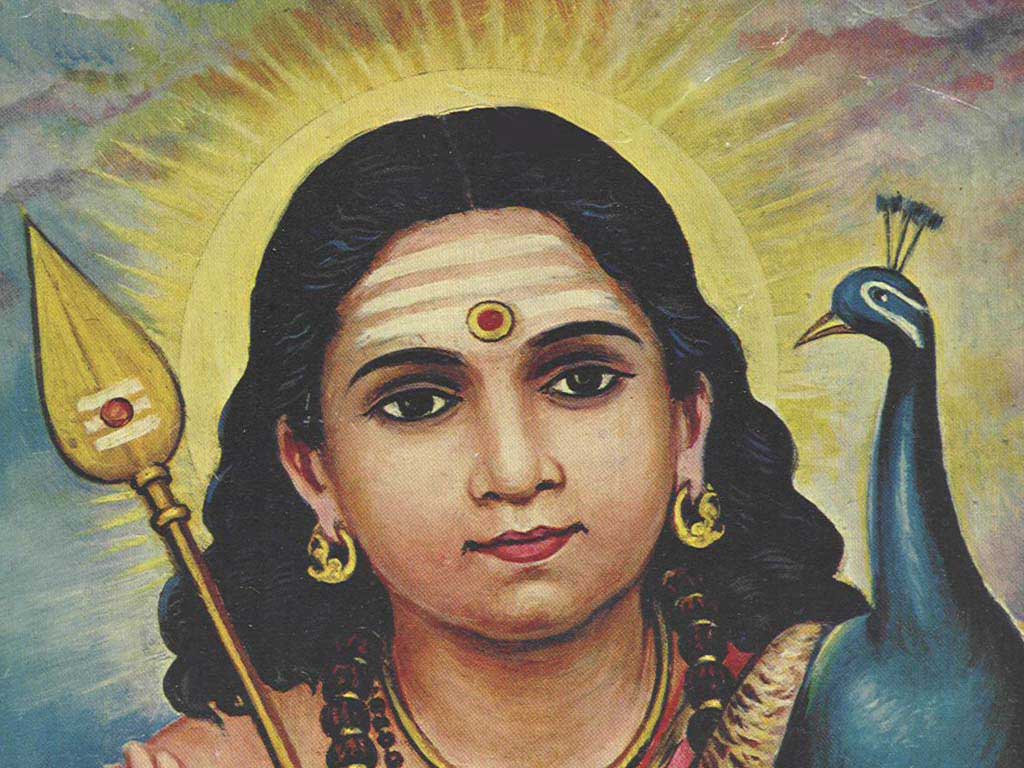

Skanda or Guha ‘the Hidden One’, we learn, appears on earth in a variety of guises to defeat Terror personified with the sharp application of his unfailing Jñāna-Śakti, the brilliant ‘spear’ of wisdom that is fashioned from the rays of the sun. He is, in fact, represented as having the same color as the rising sun (Sanskrit: bāla-sūriya-sama-prabhā) and he is repeatedly urged to ‘come’ by those informed enthusiasts (bhaktas) who liken his appearance to the rising of the sun at dawn.

After making child’s play of his comic mission of vanquishing Terror and establishing Justice, the Hidden One takes his divine leisure engaging in royal pastimes like hunting, warfare and romantic courtship, all three of which he excels at through the application of his prodigal stealth and cunning. He is the master Thief who operates by day or night, engaged in his own secret Royal Business that is beyond the ken of ordinary mortals. His quarry is the unsuspecting human soul, the earth-born ‘maiden’ whose heart, firmly set upon Him only, is finally ‘stolen’ away to achieve her heart’s deepest desire (Skt: iccha-sakti).

Madly in Love with the Thief of Hearts

Though His intentions are honourable, Skanda nevertheless appears as an erotic, amorous, pleasure-seeking and irresponsible youth in chapter 81 of the BrahmĀ Purana. In ancient Tamil poetry, he is credited with creating love-frenzy in girls, as in the following lines of one of the oldest poems in the Tamil language:

“Here festivals are always held

Harmonious with the dances wild

Of frenzied maids by the Red-god stirred,

The flutes do pipe, the lyres do twang,

The drums roll loud, and the tabors sound.”

-Pattinapalai 178-182

Even today, the god’s continuing association with fertility is too obvious to ignore.

Profile of a Hero

A composite character portrait of this baffling deity therefore must include such diverse traits as:

- Learning and Wisdom

The god’s long association with the elucidation of wisdom is expressed in his epithet as the Jñāna Pandita or learned expositor of gnostic wisdom. This trait may be traced to the Vedic conception of Agni, who is called ‘all-knowing’ (Sanskrit: viśva-vid), ‘poet-sage’ (Skt: kavi) and ‘possessing intelligence of a sage’ (Skt: kavi-kratu). - Playfulness

Naturally, as the Sanat Kumāra or Perpetual Child, the god tends to be playful and may even appear to be naughty, while remaining throughout as the ever-innocent Bāla or Fool (Tamil: mūdan). He is forever immersed in his inconceivable Tiru Vilaiyātal or Divine Play of which he is the Magister Ludi, the Master of the Cosmic Game. - Knavery and underground activities

Modern scholars have been puzzled by the god’s mischievous associations. In the canonical Atharva Veda and again in Kalidasa’s Mrcchakatika he is repeatedly called dhūrta, which can only mean ‘rogue’. Even today, living Tamil oral tradition maintains that he is a rogue (kalan) and a trouble-making trickster (Tamil: paullāthakkāran). Indeed, he is the Champion of Rogues, the Divine Trickster and Supreme Schemer who cheats even Death. In legend, he comes as a thief in the night to ‘steal’ the chief’s princess-daughter; in Bengal he remains best known as the patron god of thieves and women of ill repute. - Mystery and secrecy

As the Mauna Guru or Silent Teacher, Guha ‘the mysterious one’ conveys deep secrets to those whom he touches with a mere glance or word. As Kārttikeya the Supreme Commander of the army of the devas, his prowess extends to the unfailing execution of clandestine strategies, often in the face of – apparently – staggering odds. - Benevolence

Although he is portrayed as a rogue and a trickster, Skanda is nevertheless regarded as a boon-giving auspicious deity by His devotees. Once he is honored and served, he reciprocates measure for measure by granting His servants the boon of their heart’s desire. To most devotees, this is his most endearing trait: he is the one true companion or thunai who is always ready to promote the welfare of his friends, even though his ways are breath-takingly mysterious.

Skanda: The Ideal God

Out of this baffling collection of traits, one may begin to draw together in the mind’s eye a distinctive character profile of this fascinating multi-faceted divinity. Dedicated students of the god are constantly endeavoring to incorporate these traits into one dazzling vision of the great god himself.

Just as god Skanda is of unknown origin, so are the origins of his ancient cult. But it is worth noting that a great similarity exists between the Indian Skanda and the Iranian Sraosa, the obedient and watchful messenger of Ahura Mazda. Likewise, a complex web of parallel motifs also connects Indian Skanda to Iskandar, as Alexander the Great is known in West and Central Asia. This, however, is a separate topic of study onto itself.

The literature and lore dedicated to Skanda is prodigious; the Skanda Purāna alone is second in size only to the Great Epic. During the Gupta dynasty, the classical peak of Indian civilization, Skanda was considered the ideal Indian god. In the post-Gupta period, his cult declined in North India but began to rise in the South. Just as Puranic lore relates that the god migrated south from the trans-Himalaya, so has his cult followed him to the South where it still flourishes to this day, presumably in his undying beneficient Presence.

This article first appeared as “The Kataragama God in Hindu Lore” in The Island (Colombo) of 17 November 1993.

Patrick Harrigan, M.A. (University of Michigan), has been acting editor of the Kataragama Research and Publications Project since 1989.