|

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

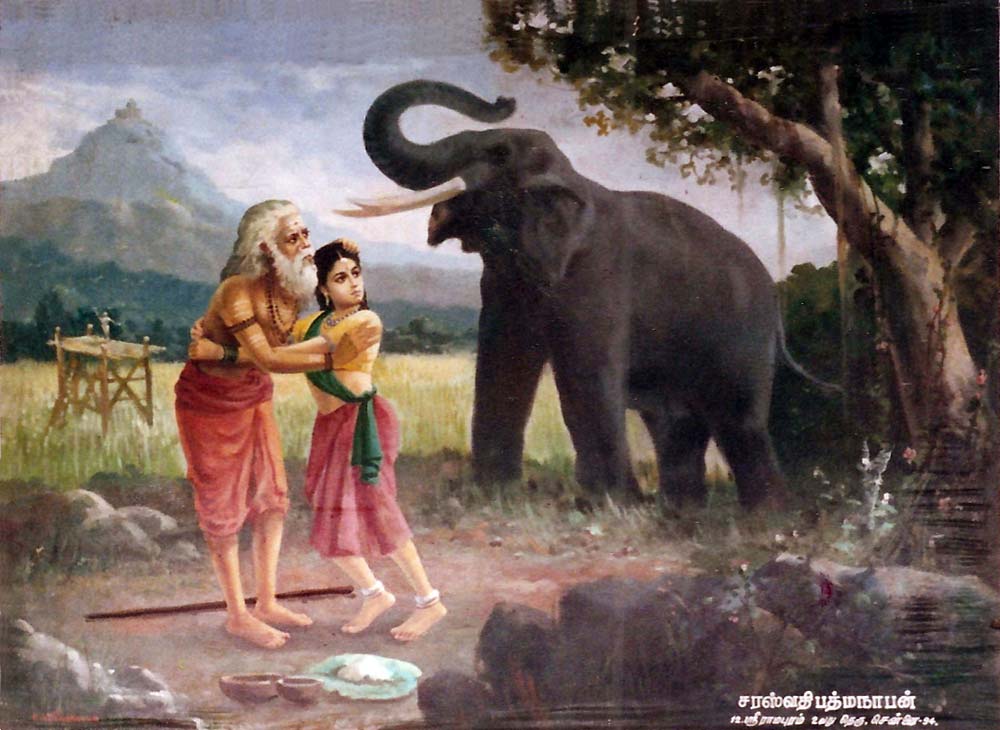

Murugan and Valli

Part One of a three-part series by Kamil V. Zvelebilfrom Tiru Murugan (Madras: International Institute of Tamil Studies, 1981) p. 40-46

The story of Murugan's courtship and his union with the daughter of the hunters, Valli, is the most important of all Tamil myths of the second marriage of a god. In the Sanskrit tradition, Skanda is either an eternal brahmacarin (bachelor) or the husband of a rather colourless deity, Devasena, the Army of the Gods. In Tamil, in contrast, the earliest reference to a bride of Murugan is to Valli and there can be no doubt whatsoever that Valli is the more popular and more important of Murugan's two brides. Hence, I do regard the lovely myth of Murugan and Valli as an indigenous-autochthonous myth, a Dravidian myth; it also contains some of the oldest indigenous fragments of myth to survive, and some of the most ancient conceptual and ideological apparatus of the Tamils. The standard version, considered by Tamil devotees of Murugan as canonical and definitive (although not the only one current!), is found as the very last (24th) canto of the sixth book of Kacciyappa's Kantapuranam (composed around 1350 AD in Kanchipuram); entitled Valliyammai tirumanappasalam, it has 267 stanzas. Here is its brief summary: There is a mountain called Valli Malai or Valli Verpu, not far from the village of Merpati, in the Tontainatu country. In a village beneath the hill lived a hunter called Nampi; all his children being boys, he longed for a little girl. On the mountain slope, an ascetic by name of Śivamuni was engaged in austerities. One day a gazelle went by, and the ascetic was aroused by its lovely shape; his lascivious thoughts made the gazelle pregnant. The daughter of Mal incarnated in the embryo. In due time, the gazelle gave birth to a girl in a pit dug out by the women of the hunter-tribe when they searched for the tubers of edible yam (valli). The female deer, having round out that she had given birth to a strange being, abandoned the child which was discovered by the hunter-chief Nampi and his wife. Overwhelmed with joy, they took the little girl to their hut and named her Valli. When Valli reached the age of twelve, she was sent to the millet field - in agreement with the custom of the hillmen – to guard the crop against parrots and other birds, sitting in an elevated platform called itanam (paran), and chasing the birds and other beasts away. The sage Narada, who visited Valli Malai and saw the girl, went to Tanikai and informed god Murugan about Valli's exceptional beauty and her devotion to the god of the hunters. Murugan assumed the form of a hunter and, as soon as he arrived at Valli's field, he addressed the lovely girl enquiring after her home and family. However, at that moment Nampi and his hunters brought some food for Valli (honey, millet flour, valli roots, mangoes, milk of the wild cow) and Murugan assumed the form of a tree (venkai, Pterocarpus bilobus). When Nampi and his company disappeared, the god reappeared in human form, approached Valli and told her that he would like to love her. Valli was shocked, lowered her head, and answered that it was improper for him to love a woman from the low tribe of the haunters. At that moment they heard the sound of approaching drumming and music. Valli warned Murugan that the hunters are wild and angry men, and the god transformed into an old Saiva devotee. Nampi and his hunter's took his blessings and returned home. |